1、Damnatio Memoriae

除憶之刑

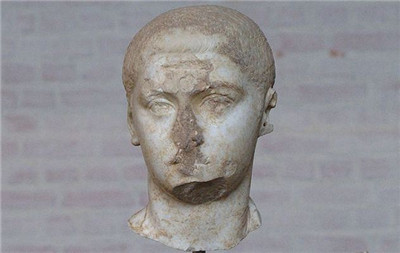

A practice common with nearly every ancient culture, and even some today,damnatio memoriae was the ritualistic and symbolic removal of a person from history. Seen as the worst punishment imaginable, worse than execution, the damned’s name was scratched from inscriptions, frescos with his face were painted over, and any statue was defaced, as if it was really him. It was normally reserved for the worst emperors in Roman history; Caligula and Nero escaped this punishment by having powerful friends, even after death.

這是一種幾乎每個古老文明都有的,甚至在今天的某些地區(qū)依然存在的刑罰。除憶之刑是象征性地、通過某種儀式將某人從歷史中移除,它被看作是世上最嚴(yán)重的懲罰,甚至比死刑還要嚴(yán)重。受刑的人的名字會從銘文中擦去去,壁畫中的他的頭像會被涂抹覆蓋,而他的雕塑則會被損壞丑化,好象那才是真正的他。通常只有羅馬歷史上最昏庸無道的君主才會被施加這種刑罰,即使是在他們死亡以后。而卡里古拉(Caligula)和尼祿(Nero)因?yàn)橛袡?quán)力強(qiáng)大的朋友的幫助而逃過了該刑罰。

Only three emperors are known to have been officially given this punishment, including Maximian, whose friend and co-emperor Diocletian is said to have been so stricken with grief that he died shortly after hearing the news. Obviously, it didn’t work as well in practice as it did in theory; we still know about everyone who was the subject of damnatio memoriae. Some scholars feel it may have served a cathartic purpose for the public, enabling them to vent their frustration over the failures of their leaders.

目前已知的只有三位君主曾被正式地施以該刑罰,包括有馬克西米安(Maximian),據(jù)說他的朋友戴克里先(Diocletian)聽到這個消息以后傷心過度,不久后就死去了。很明顯,這個刑罰實(shí)際并沒達(dá)到它理論上的效果,因?yàn)槲覀內(nèi)匀恢獣阅切┦艿匠龖浿痰娜恕R恍W(xué)者認(rèn)為除憶之刑能起到讓公眾泄憤的作用,讓他們發(fā)泄出對領(lǐng)導(dǎo)者的失敗的失意感。