巴拿馬草帽

Hold onto your headwear

守住你的帽子

Ecuador makes them and wants you to know it

厄瓜多爾制造了這種帽子并希望你去了解它

HATS have been woven in and around Montecristi, a hillside town in Ecuador near the Pacific Ocean, since as long ago as the 17th century. Locally the cream-coloured titfers, which are made from the soft fibres of a palm-like plant, are called toquilla-straw hats. To the rest of the world, however, they are known as Panama hats. Now Ecuador wants to reclaim the brand.

蒙特克里斯蒂是厄瓜多爾的一座山地小鎮(zhèn),位于太平洋附近��。從17世紀(jì)開始,這座小鎮(zhèn)及其周邊就開始編織帽子了。這種帽子是淡黃色的,用一種叫多基利亞的棕櫚狀植物的柔軟纖維編織而成�,當(dāng)?shù)厝朔Q它為多基利亞草帽���。但對(duì)于世界其它地方的人來說���,這種帽子被稱為巴拿馬草帽����。如今厄瓜多爾希望收回這個(gè)牌子���。

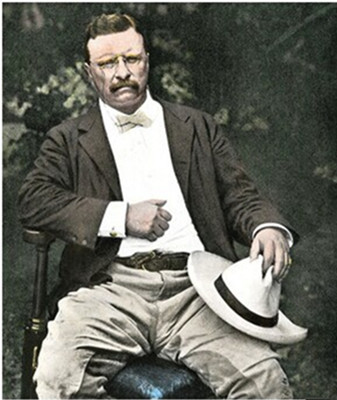

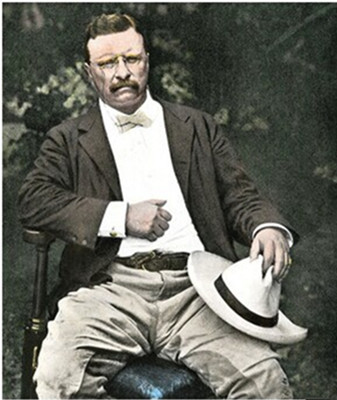

The hats became known as “Panamas” because that was where they were primarily sold to international markets. By the 1840s Ecuadorean entrepreneurs were sending them to Panama in the tens of thousands. Prospective gold-diggers bought them as they crossed the isthmus on their way to California. Theodore Roosevelt helped make them fashionable on a visit, in November 1906, to see the construction of the canal.

這種帽子被稱為“巴拿馬帽”是因?yàn)樗畛蹁N售的國際市場(chǎng)是巴拿馬��。在19世紀(jì)40年代之前厄瓜多爾企業(yè)家們將數(shù)以萬計(jì)的帽子運(yùn)往巴拿馬�。抱著期望的淘金者們?cè)诖┰降貚{去往加州時(shí)購買這種帽子�����。西奧多·羅斯福在1906年訪問參觀巴拿馬運(yùn)河建筑情況時(shí)戴著這種帽子�����,促進(jìn)了它的流行�����。

The hats fell out of favour in the second half of the 20th century, but data from Ecuador's Central Bank suggest demand is rising. The country exported finished hats worth $6m in 2013, up from a piffling $517,000 in 2003. The headwear goes mostly to Italy, Britain and the United States, where they can fetch anything from a few dollars to several thousand for the most intricate designs. According to Andrés Ycaza of the Ecuadorean Intellectual Property Institute, a skilled weaver will earn only about $800 for a hat worth close to $2,000, which can take months to make. Without a premium attached to its Ecuadorean origins, it is hard to drive prices higher.

這種帽子在20世紀(jì)后期開始失寵�,但厄瓜多爾中央銀行的資料表明需求仍在增長�。2013年國家貿(mào)易出口的成品帽子總價(jià)值為六百萬美元,而2003年僅為517,000美元��。這種帽子主要售往意大利��、英國和美國����,在那里它們的價(jià)格不等,最低只有幾美元�����,而最精細(xì)復(fù)雜的款式可以達(dá)到幾千美元��。據(jù)厄瓜多爾知識(shí)產(chǎn)權(quán)協(xié)會(huì)的安德列·伊卡薩稱�,一個(gè)熟練的編織工人編織一頂價(jià)值接近2000美元的帽子需要數(shù)月時(shí)間����,而他從中只能掙到800美元。因?yàn)槎蚬隙酄杹碓吹夭粫?huì)為帽子帶來額外價(jià)值��,因此價(jià)格很難增高��。

Mr Ycaza's answer is to try and promote the hat's roots. In 2012 the weaving of the toquillahat won a place on UNESCO's list of “intangible cultural heritage”. Now IEPI is trying to gain protected designation-of-origin status for the Montecristi hat in trade negotiations with the European Union, which protects everything from Roquefort cheese to Isle of Man Queenies, a type of scallop. “This is the moment to make it known to the entire world that the Montecristi hat is made here in Ecuador,” says Mr Ycaza.

伊卡薩給出的解決方案就是嘗試發(fā)揚(yáng)帽子的產(chǎn)地��。2012年這種手工編織的多基利亞草帽還被列入聯(lián)合國教科文組織人類非物質(zhì)文化遺產(chǎn)名錄。如今IEPI正試圖在與歐盟的商業(yè)談判中為蒙特克里斯蒂的帽子爭取原產(chǎn)地名稱保護(hù)制度�,這種制度保護(hù)一切東西�,如曼島奎尼扇貝和洛克福羊乳干酪�。“是時(shí)候讓全世界都知道蒙特克里斯蒂帽子產(chǎn)地是厄瓜多爾了����,”伊卡薩說。

The idea hasn't won universal support. Although Montecristi is home to 500 or so weavers, the city of Cuenca in the southern Andes produces and exports most finished toquilla hats. There they worry that the Montecristi brand won't much help them. “If a weaver from Manabí [Montecristi's home province] for whichever reason moves to Cuenca, the hat he makes in Cuenca isn't going to be worse than the one he weaves in Manab,” says Gabriela Molina of Homero Ortega, a family-owned hatmaker.

這個(gè)想法沒有獲得廣泛支持�。盡管蒙特克里斯蒂是500多名手工編織藝人的家鄉(xiāng)�����,南安第斯山脈的城市昆卡也制造和出口大量成品多基利亞草帽,他們擔(dān)憂蒙特克里斯蒂品牌對(duì)他們沒什么幫助����?���!叭绻幻麃碜择R納比?。商乜死锼沟俚乃鶎偈。┑氖止ぞ幙椝嚾诉w移到了昆卡��,他在昆卡制作的帽子不會(huì)比在馬納比制作的差���,”家族制帽商奧梅羅·奧特加的加夫列拉·莫利納說�����。