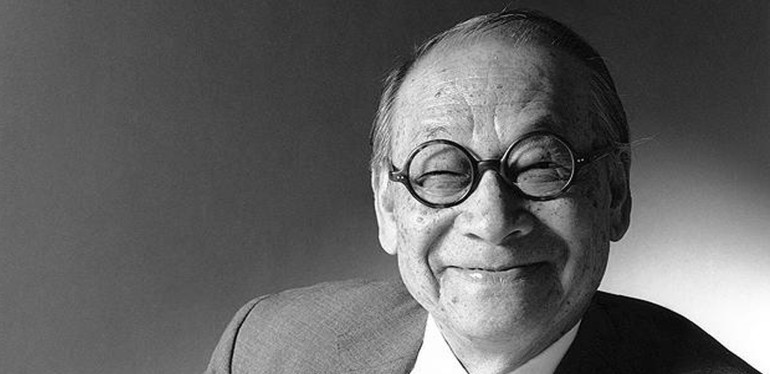

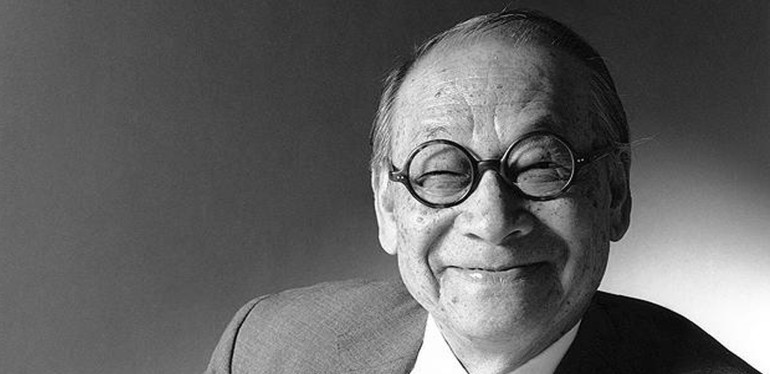

Architect’s work will live on

貝聿銘的百年建筑人生

Most architects hope to add to the character of a city, but Ieoh Ming Pei, one of the world’s best-known architects, changed many cities around the world with his iconic designs. The JFK Presidential Library in Boston, US (1979), the Louvre Pyramid in Paris (1989), the Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong (1990) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Qatar (2008), are just a few of his many creations.

大多數(shù)建筑師都希望為一座城市的特性錦上添花,但全球聞名的建筑大師貝聿銘卻用其標志性的設(shè)計改變了世界各地的眾多城市。美國波士頓的肯尼迪圖書館、巴黎的盧浮宮玻璃金字塔、香港的中銀大廈、卡塔爾多哈的伊斯蘭藝術(shù)博物館不過是他眾多作品中的寥寥幾個罷了。

The man behind these landmark buildings died on May 16, at age 102. US author and critic Paul Goldberger called Pei’s death “the end of an architectural era” on the Instagram social network. “... A sad moment, but a career – and a life – worthy of celebration,” he wrote.

作為這些地標性建筑背后的建筑師,貝聿銘于5月16日逝世,享年102歲。在社交媒體Instagram上,美國作家、評論家保羅·戈德伯格稱貝老去世標志著“一個建筑時代的落幕”。“……這是一個悲傷的時刻 —— 但他的事業(yè)、他的人生值得頌揚,”他寫道。

Pei once noted that a typical style of design “is of no help to an architect”. Instead, he was known for his eclectic style, bringing together seemingly opposite ideas into each design – East and West, ancient and modern, natural and manmade.

貝聿銘曾指出,一貫的設(shè)計風(fēng)格“無益于建筑師”。恰恰相反,貝聿銘以兼收并蓄的風(fēng)格著稱,他在每一處的設(shè)計中都將看似對立的概念結(jié)合在一起 —— 東方與西方、古代與現(xiàn)代、自然與人造。

This may come from his upbringing. Born and raised in China, he went to the US to study architecture at 18. He studied at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and then completed his Master of Arts study at Harvard. “I’ve never left China,” the Chinese-American Pei once told the Financial Times. “My family’s been there for 600 years.”

這一點或許來源于他的教育背景。他在中國出生和長大,18歲時赴美學(xué)習(xí)建筑,先是在麻省理工學(xué)院進修,后在哈佛大學(xué)獲得文學(xué)碩士學(xué)位。“我從未離開過中國,”身為美籍華裔的貝聿銘在接受《金融時報》采訪時曾如此表示。“我的家族在那里生活了600年。”

Pei tried to include local and historical ideas in his designs. When designing the Suzhou Museum in the 2000s, he took inspiration from the city’s delicate classical gardens. Instead of building a giant to overshadow them, Pei built small halls with traditional white walls and dark roofs, in the style of other gardens. The glass skylights and straight lines of the roof add a modern flair to the museum.

貝聿銘試圖在其設(shè)計中加入當(dāng)?shù)匾约皻v史的元素。在本世紀初設(shè)計蘇州博物館時,他從該城市精美的古典園林中獲得了靈感。貝聿銘并沒有建起一棟摩天大樓使這些園林黯然失色,而是按照其他園林的風(fēng)格,打造了一個個傳統(tǒng)的白墻深瓦的小展廳。玻璃天窗以及屋頂?shù)闹本€元素也為博物館增添了一絲現(xiàn)代的魅力。

Besides matching his designs to the local surroundings, Pei also thought that light was a key factor to creating a lively atmosphere. He cared a lot about the sunlight in his designs. “Good architecture lets nature in,” he told People magazine.

除了令自己的設(shè)計融入當(dāng)?shù)丨h(huán)境之外,貝聿銘還認為光線是創(chuàng)造生動氛圍的關(guān)鍵因素。他十分關(guān)注設(shè)計中的采光。“優(yōu)秀的建筑與自然融為一體,”,他在接受《人物》雜志采訪時如此表示。

The glass pyramid of the Louvre Museum in Paris is a good example. It doesn’t hide the buildings around it. Instead, it reflects them in the sunlight. It also serves as a huge window, letting sunlight into the museum. Today, many people visit the Louvre and take photos of the pyramid.

巴黎盧浮宮的玻璃金字塔就是絕佳范例。它并沒有遮擋周遭的建筑,而是在陽光下映照出了它們的樣子。它還成了一扇巨型窗戶,讓陽光照進博物館。如今,許多參觀盧浮宮的游客都會和金字塔拍照。

Essentially, Pei regarded himself as a pragmatic artist. What he valued most in architecture, he said, was that the buildings could “stand the test of time”. As The New York Times sums up, he didn’t just want to solve problems but also to produce “an architecture of ideas”.

貝聿銘原本就將自己視為實用主義藝術(shù)家。他表示,自己在建筑方面最看重的一點是建筑物能夠“經(jīng)受住時間的考驗”。正如《紐約時報》所總結(jié)的那樣,他不僅想要解決問題,還想要建造出“充滿想法的建筑”。