It was delicate work, requiring them to take the most exacting pains to avoid accidental crossfertilization and to note every slight variation in the growth and appearance of seeds, pods, leaves, stems, and flowers. Mendel knew what he was doing.

這是一項極為細致的工作。為了防止意外受粉,他們必須不厭其煩地記錄豌豆種子、豆莢、葉子、莖和花在生長過程中,以及在外表方面極細微的差別。對于他所做的事情的意義,孟德爾知道得很清楚。

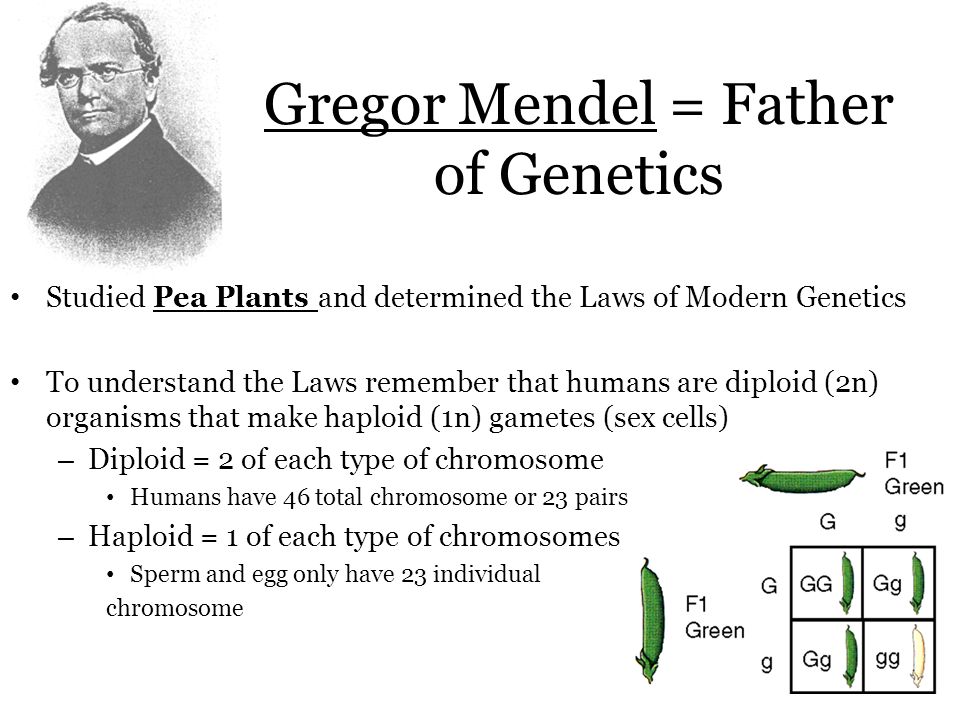

He never used the word gene — it wasn't coined until 1913, in an English medical dictionary — though he did invent the terms dominant and recessive. What he established was that every seed contained two "factors" or "elemente," as he called them — a dominant one and a recessive one — and these factors, when combined, produced predictable patterns of inheritance.

他從未用過“基因”這個詞——這個詞1913年才第一次出現于英國的一本醫學詞典——雖然發明了“顯性的”和“劣性的”這樣的概念。他的建樹在于他發現每一顆種子都包含兩個“遺傳因子”或他所謂的“本分”——一個是有時的,另一個是劣勢的,這些因子一旦相互組合,就會產生可以預期的遺傳形式。

The results he converted into precise mathematical formulae. Altogether Mendel spent eight years on the experiments, then confirmed his results with similar experiments on flowers, corn, and other plants. If anything, Mendel was too scientific in his approach, for when he presented his findings at the February and March meetings of the Natural History Society of Brno in 1865, the audience of about forty listened politely but was conspicuously unmoved, even though the breeding of plants was a matter of great practical interest to many of the members.

他把這種結果轉換成了精確的數學公式。孟德爾總共用了8年的時間從事這項研究,接著又在花卉、玉米和其他植物上進行了類似的實驗。以檢驗他的結論的正確性。甚至還不如說,孟德爾的研究方法過于科學。以致當他1865年在布爾諾自然史學會的2月和3月月度會議中宣讀他的論文時,大約40個聽眾很有禮貌地聽了他的演講,可是他們顯然無動于衷,即使對他們中的不少人來說,植物的培育實際上是他們極感興趣的一件事。

When Mendel's report was published, he eagerly sent a copy to the great Swiss botanist Karl-Wilhelm von Nageli, whose support was more or less vital for the theory's prospects.

孟德爾的報告出版以后,他迫不及待地給瑞士偉大的植物學家卡爾·威廉·馮·耐格里寄了一份。從某種意義上說,耐格里的支持對孟德爾理論的前途有著至關重要的作用。