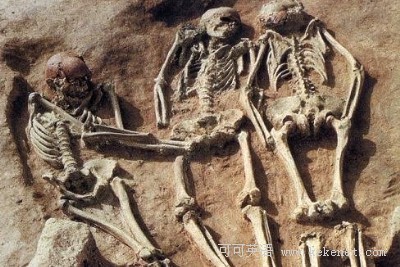

Study coauthor José María Bermúdez de Castro, of the National Research Center on Human Evolution, said that marks near the base of some skulls hint that the diners decapitated humans to get the brain goodness inside. "Probably then they cut the skull for extracting the brain…. The brain is good for food."

西班牙“國家人類進(jìn)化研究中心”研究人員之一的卡斯特羅稱頭顱底部的刻紋顯示這些人曾經(jīng)被割去了頭顱以便食人者從中取得營養(yǎng)骨髓。“也許他們當(dāng)時(shí)是為了人腦才砍頭。人腦是相當(dāng)好的食物。”

The researchers believe that eating other humans wasn't a big deal back then, and probably wasn't linked to religious rituals or marked by elaborate ceremonies. They draw that conclusion from the fact that butchered human bones were tossed in the scrap heap along with animal remains.

研究人員認(rèn)為遠(yuǎn)古時(shí)代食人并不是什么嚴(yán)重的事情,而且很可能不具有宗教意義。他們之所以得出這個結(jié)論,是因?yàn)槿祟惡」桥c動物殘骸被丟在了一起。

There is some debate as to how frequently human was on the menu, but these researchers note that the Sierra de Atapuerca region had a great climate and that cannibalism didn't likely result from a lack of alternatives.

也有人指出,同類相食并不常見,除非饑餓難耐。但研究人員稱格蘭多利納洞穴附近區(qū)域氣候適宜,食物資源豐富,所以遠(yuǎn)古人類不太可能因?yàn)槿鄙龠x擇而去食用同類。