Finance and Economics;Free exchange;The real wealth of nations;

“Wealth is not without its advantages,” John Kenneth Galbraith once wrote, “and the case to the contrary, although it has often been made, has never proved widely persuasive.” Despite the obvious advantages of wealth, nations do a poor job of keeping count of their own. They may boast about their abundant natural resources, their skilled workforce and their world-class infrastructure. But there is no widely recognised, monetary measure that sums up this stock of natural, human and physical assets.

約翰·肯尼斯·加爾布雷恩曾經(jīng)寫道:“盡管事實(shí)反復(fù)證明財(cái)富并非一無(wú)是處,而其劣勢(shì)沒(méi)人說(shuō)地明白,其優(yōu)勢(shì)誰(shuí)又真正知道呢。”即便財(cái)富優(yōu)勢(shì)清晰可辨,然而各個(gè)國(guó)家在清點(diǎn)財(cái)富時(shí),卻總做著一筆“糊涂賬”。他們也許會(huì)驕傲地宣稱,我國(guó)自然資源豐富,勞動(dòng)力技術(shù)嫻熟并且基礎(chǔ)設(shè)施世界一流。但是,我們卻沒(méi)有一個(gè)一致認(rèn)可的貨幣量度來(lái)總括這些自然,人力和實(shí)物資產(chǎn)。

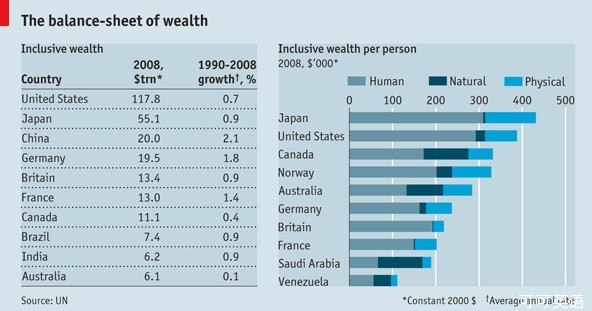

Economists usually settle instead for GDP. But that is a measure of income, not wealth. It values a flow of goods and services, not a stock of assets. Gauging an economy by its GDP is like judging a company by its quarterly profits, without ever peeking at its balance-sheet. Happily, the United Nations this month published balance-sheets for 20 nations in a report overseen by Sir Partha Dasgupta of Cambridge University. They included three kinds of asset: “manufactured”, or physical, capital (machinery, buildings, infrastructure and so on); human capital (the population's education and skills); and natural capital (including land, forests, fossil fuels and minerals).

By this gauge, America's wealth amounted to almost $118 trillion in 2008, over ten times its GDP that year. (These amounts are calculated at the prices prevailing in 2000.) Its wealth per person was, however, lower than Japan's, which tops the league on this measure. Judged by GDP, Japan's economy is now smaller than China's. But according to the UN, Japan was almost 2.8 times wealthier than China in 2008 (see charts).

Officials often say that their country's biggest asset is their people. For all of the countries in the report except Nigeria, Russia and Saudi Arabia, this turns out to be true. The UN calculates a population's human capital based on its average years of schooling, the wage its workers can command and the number of years they can expect to work before they retire (or die). Human capital represents 88% of Britain's wealth and 75% of America's. The average Japanese has more human capital than anyone else.

官員們經(jīng)常說(shuō)人民是國(guó)家最大的財(cái)富。除尼日利亞,俄羅斯和沙特阿拉伯外,該報(bào)告中的其他國(guó)家均證明了此言非虛。根據(jù) 一國(guó)國(guó)民平均受教育年限,工人應(yīng)得工資和該國(guó)國(guó)民退休(或去世)前的工作年數(shù),聯(lián)合國(guó)計(jì)算出了該國(guó)的人力資本。人力資本占英國(guó)財(cái)富的88%,美國(guó)的 75%。而日本人均蘊(yùn)藏的人力資本比任何其他國(guó)家都要高。

該報(bào)告中,僅有三個(gè)國(guó)家在1990— 2008年間,沒(méi)有損耗自然資本,日本也位列其一。盡管如此,除俄羅斯外,其他國(guó)家的財(cái)富均有增加,因?yàn)槿肆臀镔|(zhì)資本的積累抵消了自然資本損耗所帶來(lái)的損 失。在調(diào)研的20個(gè)國(guó)家中,14個(gè)國(guó)家的財(cái)富增長(zhǎng)速度超過(guò)人口增速,使得2008年的人均財(cái)富高于1990年。比如說(shuō),德國(guó)的人力資本增長(zhǎng)了50%多。中 國(guó)的“制造”資本神一樣地增長(zhǎng)了540%。

By putting a dollar value on everything from bauxite to brainpower, the UN's exercise makes all three kinds of capital comparable and commensurable. It also implies that they are substitutable. A country can lose $100 billion-worth of pastureland, gain $100 billion-worth of skills and be no worse off than before. The framework turns economic policymaking into an “asset-management problem”, says Sir Partha.

聯(lián)合國(guó)評(píng)估了從鋁土礦到智力資源,一切事物的價(jià)值,此次實(shí)踐使三種資本具備了可比性和 可衡量性,也意味著它們之間可以互相替代。一個(gè)國(guó)家若失去了價(jià)值1000億美元的牧場(chǎng),卻獲得了1000億美元的技術(shù),那她的狀況并不比之前差。帕薩爵士 說(shuō):“該框架將經(jīng)濟(jì)政策制定轉(zhuǎn)變成資產(chǎn)管理問(wèn)題。”

A country like Saudi Arabia, for example, depleted its stock of fossil fuels by $37 billion between 1990 and 2008, while adding to its stock of school-leavers and university graduates (its human capital grew by almost $1 trillion). In some richer countries, however, investments in human capital appear to have hit diminishing returns, the report argues. Perhaps governments should redirect their investment into natural capital instead, restocking their forests rather than their libraries.

比如,沙特阿拉伯,在1990——2008年間,雖然損耗了 370億美元的化石燃料,但高中和大學(xué)畢業(yè)生的人數(shù)大大增加(人力資本增長(zhǎng)了近1萬(wàn)億美元)。報(bào)告指出,在一些更富裕的國(guó)家,人力資本的投資收益卻日漸萎 縮,也許這部分國(guó)家應(yīng)再度投資自然資產(chǎn),重新“武裝”森林,而不是圖書館。

The idea that natural assets are substitutable makes some environmentalists (including some contributors to the report) nervous. Many of the services the environment provides, like clean water and air, are irreplaceable necessities, they point out. In theory, however, the undoubted value of these natural treasures should be reflected in their price, which should rise steeply as they become more scarce. A good asset manager will then husband them carefully, knowing that it will take an ever-increasing amount of human or physical capital to make up for further losses of the natural kind.

“自 然資產(chǎn)可替代論”讓一些環(huán)保主義者(包括參與報(bào)告的人)不由捏一把冷汗。他們指出,自然所給予人類的供養(yǎng),如潔凈的水和空氣是無(wú)法替代的必需品。然而,理 論上,這些自然財(cái)富不容置疑的價(jià)值應(yīng)該通過(guò)價(jià)格體現(xiàn)出來(lái),而價(jià)格會(huì)隨著它們的稀缺而水漲船高。一位資深的資產(chǎn)管理人會(huì)謹(jǐn)慎使用這些資產(chǎn),因?yàn)樗雷匀毁Y 本的空洞將變本加厲地吸取人力資本或物質(zhì)資本。

In practice, however, natural assets are often hard to price well or at all. As a consequence, the UN report has to steer clear of assets like clean air that cannot be directly owned, bought or sold. It confines itself to resources like gas, nickel and timber, for which market prices exist. But even these market prices may not reflect a commodity's true social value. Beekeeping is one example beloved by economic theorists. Bees create honey, which can be sold on the market. But they also pollinate nearby apple trees, a useful service that is not purchased or priced.

但是,實(shí)際上,我們很難或根本無(wú)法給自然資產(chǎn)標(biāo)上合適的價(jià)格。聯(lián) 合國(guó)的報(bào)告中避開了像潔凈空氣這樣無(wú)法直接擁有和買賣的自然資產(chǎn),而只計(jì)算可以用市場(chǎng)價(jià)表示的自然資產(chǎn),如天然氣,鎳和木材。即便如此,也許市場(chǎng)價(jià)無(wú)法反映出商品 真正的社會(huì)價(jià)值。經(jīng)濟(jì)理論家愛(ài)以“養(yǎng)蜂”為例,蜜蜂釀下可以在市場(chǎng)上兜售的蜂蜜,但它們也為周邊的蘋果樹授粉,而這個(gè)有益的舉動(dòng)卻不能被出售,也無(wú)法標(biāo) 價(jià)。

No one is more aware of these limitations than the report's authors. Their estimates are illustrative, not definitive, says Sir Partha. The calculations are inevitably crude, just as the first guesstimates of GDP were crude over 70 years ago. He hopes more economists will do the hard but valuable work of pricing the seemingly priceless. The profession does not really reward this work, says Sir Partha. But some economists do it anyway. Taylor Ricketts of the University of Vermont and his co-authors have even calculated the value of pollination, showing that one Costa Rican coffee-grower benefited by $62,000 a year from the feral honey bees in two nearby patches of forest.

沒(méi)有誰(shuí)比該報(bào)告的作者更清楚它的局限性。帕特爵士說(shuō):“他們的估算是對(duì)現(xiàn)有資本的補(bǔ)充性解釋,并不是最 佳版本。”報(bào)告的結(jié)果不免有不準(zhǔn)確的地方,正如70多年前人們第一次約摸著估算GDP(國(guó)內(nèi)生產(chǎn)總值)一樣。他希望更多經(jīng)濟(jì)學(xué)家能做出艱苦且有價(jià)值的工 作,為世界的無(wú)價(jià)資產(chǎn)標(biāo)價(jià)。帕特爵士還說(shuō):“這項(xiàng)工作在業(yè)界并非真地有利可圖。”不管怎樣,還有經(jīng)濟(jì)學(xué)家為此奉獻(xiàn)著,佛蒙特大學(xué)的泰勒·立克次和他的合著 者們甚至計(jì)算出了蜜蜂授粉的價(jià)值。結(jié)果顯示,哥斯達(dá)黎加兩小片樹林中的野蜜蜂就能為一位咖啡種植主帶來(lái)62000美元的利潤(rùn)。

Now that economists have shown that such wealth can be measured, they must decide what it should be called. In his earlier academic work Sir Partha calls it “comprehensive wealth”. The UN report dubs it “inclusive wealth”. If the notion catches on, neither name may be needed. “Pretty soon,” says Sir Partha, “we ought to drop both adjectives and just call it wealth'.”

既然經(jīng)濟(jì)學(xué)家已經(jīng)證明自然財(cái)富可以計(jì)算,那他們必須為它取個(gè)名字。在其早前的學(xué)術(shù)專著中帕特爵士曾稱它為“全部財(cái) 富”。聯(lián)合國(guó)的報(bào)告中則叫它“天地財(cái)富”。一旦這個(gè)概念流行開來(lái),這兩個(gè)名稱都可能被淘汰,“很快”,帕特爵士說(shuō),“我們應(yīng)把形容詞都去掉,就叫它“財(cái) 富”!”