Finance and Economics; The global crash; Japanese lessons;

財經;全球危機;日本教訓;

After five years of crisis, the euro area risks Japanese-style economic stagnation;

經過五年危機,歐元的狀況正冒著日本當年經濟模式停滯的風險;

Five years ago, things looked rosy. In the first week of August 2007 forecasts by investors and major central banks predicted growth rates of 2-3% in America and Europe. But on August 9th 2007 everything changed. A French bank, BNP Paribas, announced big losses on subprime-mortgage investments. The same day, the European Central Bank (ECB) was forced to inject 95 billion EURO(130 billion DOLLAR at the time) of emergency liquidity. The crisis had begun.

五年前,世界經濟比較樂觀。2007年8月的第一周,觀察人員和主要銀行人員預計美國和歐洲會有2-3%的增長率。但在同年8月9日事態改變。法國巴黎銀行宣布其在次貸投資商損失慘重。同一年,歐洲央行強行注入950億歐元(在當時約合13000億美元)作為緊急流動資金。危機已然開始。

During the first year, policymakers looked to Japan as a guide, or rather a warning. Japan's debt bubble had caused a “lost decade”, from 1991 to 2001. Analysts commonly drew three lessons. To avoid Japanese-style stagnation it was vital, first, to act fast; second, to clean up battered balance-sheets; and, third, to provide a bold economic stimulus. If Japan is taken as the yardstick, America and Britain have a mixed record. The euro area looks as if it might be turning Japanese.

危機開始的第一年,政策制定者把日本看作是一個參照物,或者說是個警告。從1991到2001期間,日本的債務泡沫帶來了“低迷的十年”。分析者得出了三點教訓。為了不上演日本式的蕭條,一要快速采取行動;二要清理糟糕的資產負債;還有第三點出臺有力的經濟刺激行動。如果日本被看作標尺,美國和英國則有個混雜的記錄。歐元區看來是要重蹈日本當年的狀況。

Debts took years to build up. Take the American consumer. Debt was around 70% of GDP in 2000, and grew at around 4 percentage points a year to reach close to 100% of GDP by 2007. The same was true of European banks and governments: debts rose hugely but steadily. It was not hard to spot debt mountains forming.

這幾年負債不斷增加。以美國消費者為例,在2000年,負債占到GDP的約70%,而在2007年,這一指標在一年上升了4%達到接近GDP100%的水平。同樣的事情發生在歐洲銀行和政府上:負債升幅穩定但數量巨大。不難想象負債這座大山已開始形成。

The crisis erupted with the realisation that subprime exposures were widespread. Many assets were worth less in the market than they had been bought for. Debts started to look unsustainable and interest rates jumped. This meant governments, consumers and banks, after building up debt slowly, suddenly faced much higher costs, as debts matured and they were forced to refinance at higher rates.

危機隨著次貸問題的蔓延而火速爆發。很多資產相比買來的時候已不值幾個錢。負債開始變得不可支撐而且利率可開始飆升。這意味著隨著負債不斷增加,政府、消費者和銀行突然面臨著過高成本,因為當債務到期,他們要面臨更高利率的貸款。

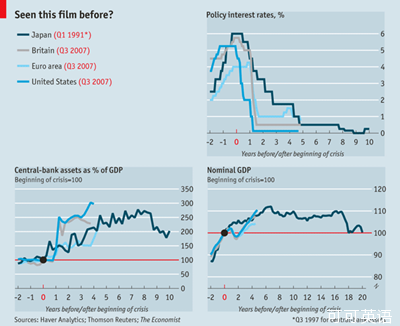

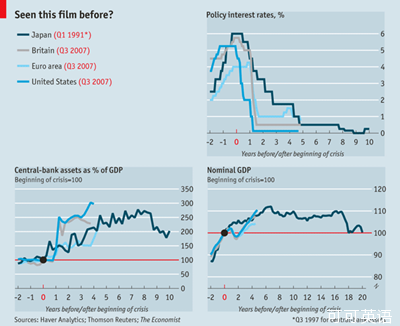

The reaction was quick. By the end of 2008 the Federal Reserve, the ECB and the Bank of England had slashed official interest rates. Their aim was to offset the spike in debt costs that companies and consumers were facing. The cuts were fast by Japanese standards (see top right-hand chart). It seemed the first lesson had been learnt.

相關部門對此作出快速反應。在2008年末,美聯儲、歐洲央行和英國銀行已經削減了官方利率。他們的目標是沖抵公司和消費者要面臨的高債務支出。這種削減相對于日本當年的反應速度是很快的。看上去我們吸取了第一個教訓。

Falling asset prices meant that many banks and firms had debts that outweighed their assets. The Japanese experience showed that the next job was to deal with these broken balance-sheets. There are three main options: renegotiate debt, raise equity or go bankrupt.

下降的資產價格意味著很多銀行和公司擁有的負債超過了資產。日本經驗表明下一個任務是解決這些糟糕的資產負債表。這有三個主要的選擇:重新談判債務、提高權益或是破產。

In the efforts to reinvigorate balance-sheets, debt investors have reigned supreme. Debts have been honoured. Indeed, a recent report from Deutsche Bank shows that even investors in risky high-yield debt have had five great years. Bank bonds in America have returned 31%; in Europe, 25%.

為了重振資產負債表,債務投資者首當其沖。負債已被承兌。最近德意志銀行的報道稱即使是投資高風險的債券投資家,他們也曾有五年盈利的時候。美國的銀行債券重回31%,英國為25%。

As asset values fell, debt maintained its fixed value. This meant that equity, the balance-sheet shock-absorber, had to fall in value. So although debt caused the problem, equity took the pain. A Dow Jones index of bank equity is down by more than 60% since 2007, according to Deutsche Bank. Some banks' share prices are down by more than 95%.

隨著資產價值下降,負債維持在固定值。這意味著權益這個資產負債表的緩沖劑,需要下調其價值。所以盡管負債制造了問題,但權益要為其吞下苦果。據德意志銀行稱,從2007年起銀行股本的道瓊斯指數下降超過60%。一些銀行的股價也下降了超過95%

In many cases, the equity buffers were too small, so governments stepped in, taking equity stakes in banks. In both America and Europe governments stood behind their financial sectors. Balance-sheets were repaired. It seemed the second lesson from Japan had been learnt too.

在很多事件中,權益的緩沖效果太弱了,所以政府介入來干預銀行的權益。美國和歐洲政府都支持自己的財政部門。資產負債表也得到修理。看上去從日本學到的第二個教訓也奏效了。

But the clean-up just moved the problem on. Governments borrowed to fund the bail-outs. So banks' balance-sheets were strengthened at the expense of public ones. America's support for the banks cost 5% of GDP; Britain's cash injection into its ailing banks was 9% of GDP. And household debt was still high.

但是這個清理卻帶來的問題。政府借款來救市。 所以銀行的資產負債表因公共支出而得到加強。美國對銀行的救助花費了大約5%的GDP;英國對形勢不好的銀行的資金注入也達到9%的GDP數額。家庭負債依然很高。

A third lesson from Japan was to seek a strong stimulus: in a growing economy, high debt need not be a problem. Take a household's finances. A large mortgage is fine as long as breadwinners' incomes are sufficient to pay the interest and leave some to spare. Inflation helps too, as debts are fixed at their historical values but wages should rise with inflation.

日本的第三個教訓告訴我們的是要尋求一個有力的刺激行動:在高速發展的經濟下,高負債不是個大問題。以家庭財政為例,只要家里的收入能付得起利息和留存一些利潤,那么高的借貸也沒什么不好的。通貨膨脹看上去對高借貸也是有好處的,因為以歷史價值估計的債務是固定的,然而工資是會隨著通貨膨脹增加的。

Following Japan's example, central banks engaged in “quantitative easing” (QE), buying bonds for newly created cash (see bottom left-hand chart). This aims to drive up bond prices, lowering yields and making debt manageable. The QE programmes have been bolder than Japan's and corporate-bond yields have indeed fallen (see Buttonwood).

向日本經驗學習,中央銀行要使用“量化寬松”用新印好的錢來買債券。其目的是抬升債券價格,降低收益使之變得可控。量化寬松比日本出臺的政策更大膽,企業債券也下降了。

But although policymakers learnt some lessons from Japan, there are reasons to worry about the next five years. In Britain and America there are two main concerns. First, the fiscal stimulus may not be bold enough and in Britain is being withdrawn before the economy is back on its feet. Having supported banks, governments are trying to cut deficits and have little to spend. Richard Koo of Nomura, a bank, reckons Japan's experience shows that governments should increase borrowing to mop up private-sector savings.

但盡管政策制定者從日本經驗中學到了不好,但對于接下來的五年的擔心還是有理由的。在英國和美國有兩大憂慮。一是,財政刺激行動不夠有力,在英國財政刺激行動在經濟復蘇前就不見蹤影。為了支持銀行,政府努力減少赤字和政府開支。野村證券的理查德 古猜測政府應該提高借債以結束私人儲蓄。

Second, government bail-outs can have long-term costs. In some cases, broken balance-sheets are a sign of a broken business model; bankruptcy is then a better option, cleansing the economy of unproductive firms. Japan kept too many bad firms going. There are signs of that in America and Britain too. The American government's bail-outs ran to over 601 billion DOLLAR, with 928 recipients across banking, insurance and car industries. Britain has large stakes in two of its four big banks and has no clear plans to sell them.

第二,政府救市面臨著長期成本。在一些實踐中,糟糕的資產負債表是不好的商業模式的一個標志;破產是更好的出路,把經濟狀況不好的公司清除出去。日本保留了太多不好的公司,美國和英國也是。美國的救市開支超過了6010億美元,救助了銀行、保險業和汽車公司共928家的實體。出售英國四家大銀行的其中兩家有很大的風險而且沒什么好辦法出售他們。

The euro area is in a more dangerous position. Its recovery has been painfully slow (see bottom right-hand chart). Its prospects look grim: data released on August 1st showed German, French and Italian manufacturing contracting at an increasing rate (dragging Britain down with them). And to the meagre stimulus and zombification of industry can be added a third Japanese trait—policy indecision. On August 2nd Mario Draghi, the ECB's head, indicated the bank's readiness to buy bonds again as part of a co-ordinated rescue plan. Stockmarkets initially fell, suggesting the investors are unconvinced that it will save the euro area from aping Japan.

歐元區處在更危險的境地。它的復蘇慢的可怕。它的前景慘淡:8月1日公布的數據顯示德國、法國和意大利的制造業正以增長的速度在萎縮(英國也被拖下水)。對于不足的刺激行動和萎靡的行業狀況可看作是日本教訓的第三個特征——政策無能。8月2號,歐洲央行行長德拉吉暗示說銀行迅速購買債券是協調救市計劃的一部分。股市明顯下降,說明投資者不相信它能像日本一樣復蘇,拯救歐元區。