Obituary

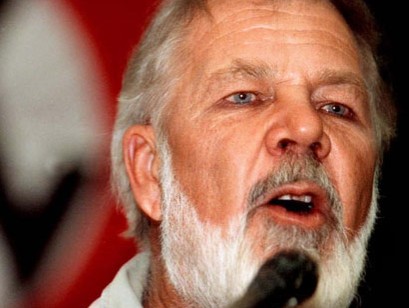

Eugene Terre'Blanche

Eugene Ney Terre'Blanche, a Boer demagogue, died on April 3rd, aged 69

On December 16th 1838, a small band of trekkers defeated a large Zulu army at the Battle of Blood River. Some say the white men prevailed because they had guns, whereas the Zulus made do with spears. But others think God intervened. Before the battle, the Afrikaners prayed, vowing always to commemorate that day if they won. Their descendants honoured that pledge. But a century and a half later, a disrespectful history professor at the University of South Africa suggested that the “Day of the Covenant” was nothing special and that God was not necessarily rooting for the tribe that created apartheid. Eugene Terre'Blanche was incensed. With a posse of followers, he burst into a lecture hall, poured hot tar on the professor and then decorated him with feathers.

1838年12月16日,一小隊白人,歷經長途跋涉,在布拉德河一役中擊敗了為數眾多的祖魯人軍隊。有人說,白人占上風是因為有槍,而祖魯人用的卻是長矛。還有人說,那是上帝的安排。戰前,白人祈禱,如果打贏了這場戰役,誓言要紀念勝利日。他們的后代子孫遵循著那個誓言。但是,一個半世紀后,南非大學的一個歷史學教授貿然提出,“起誓日”沒有什么特別之處,上帝不必眷顧那個創造隔離制度的種族。這讓尤金 特雷布蘭奇勃然大怒。他帶著一幫地方武裝分子,闖進了大學報告廳,把滾燙的柏油傾倒在教授身上,然后把羽毛沾在上面。

This act of showboating cruelty vaulted Mr Terre'Blanche to fame. Before that day in 1979, he was just a bearded racist in a country where such people were hardly in short supply. Few people noticed when in 1973 he founded a group called the Afrikaner Resistance Movement, better known later by its Afrikaner initials, AWB. He attracted as followers the kind of Boers who enjoyed donning absurd uniforms and playing soldiers. He adopted a flag that looked remarkably like a swastika, though he insisted that the design was of three interlinked 7s and represented a Christian riposte to 666, the Number of the Beast. His ideology, stripped to its essentials, was that blacks were not only inferior but also a mortal threat to the Afrikaner volk. Plenty of white South Africans agreed.

Times, however, were changing. As the 1980s rumbled on, slowly and secretly at first, the ruling National Party reached out to the African National Congress (ANC), the main black liberation movement. Mr Terre'Blanche opposed every tiny concession. Give the black terrorists and communists an inch, he predicted, and they would destroy the country. To preserve white supremacy, he threatened a civil war. And for a while, the world worried that he might make good on his threat.

Eugene Ney Terre'Blanche was born on a farm in Ventersdorp, a small town in the north, in 1941. His family was of French Huguenot stock, and was said to have been in South Africa since the 1760s. His grandfather had fought against the British during the Anglo-Boer war. The young Terre'Blanche stood out among his small-town peers, leading both the school rugby team and its debating club. On leaving school, he joined the police. He provided protection for politicians, and acted in plays staged by the Police Cultural Group, which he also ran. His thespian skills were the key to his success. He had a rich, chocolatey voice and genuine charisma. Alternately thundering and whispering from the podium, he wove together biblical, historical and apocalyptic themes. He called Nelson Mandela “Barabbas from Robben Island”. At the peak of his notoriety, said that tens of thousands of commandos would rise up when he gave the word.

In the early 1990s, when apartheid was dying, Mr Terre'Blanche tried violently to revive it. In 1993 his men crashed an armoured car through the glass fa?ade of a building near Johannesburg where the government was now openly negotiating with the ANC. Having driven out the delegates, Mr Terre'Blanche's bully boys held a barbecue. But when they left, the talks resumed. In March the next year, with about 100 of his followers, he invaded Bophuthatswana, a nominally independent “homeland” created by the apartheid government as a dumping-ground for jobless blacks. They drove around in their bakkies (pick-up trucks), killing black pedestrians at random, and seemed genuinely surprised when black policemen shot back at them. After three khaki-shorted AWB thugs were killed, the rest fled in disarray. And that was that for the white counter-revolution. Some of Mr Terre'Blanche's supporters set off bombs to disrupt the poll, killing around 20 people. But that was nowhere near enough to stop millions of blacks from turning out to vote.

The “leader”, as he styled himself, was no nicer in private. Though he won amnesty for his political crimes, he was jailed for beating one black worker into a coma and attempting to murder another. Yet unintentionally, he did some good. By making his cause look ridiculous, he weakened it. He fell off his horse at a parade. He wore green underpants with holes in them. He could fill a stadium and put on a show, but as a military commander, he was hopeless. Newspapers mocked him with punning headlines, such as “O volk! Terre'Blanche is back again”. Had he been less of a buffoon, South Africa's road to democracy might have been bloodier.

In the late 1990s he released a CD on which he read his own poems. They were packed with images of wide farms, dry riverbeds, windswept veld, frolicking gemsbok and scratching guinea fowl. Even the birds were better off than Afrikaners, he grumbled: “Even the marsh-lourie has his sleeping-place and his fellows, his lourie-people.” How far, he wondered, would he have to travel to find his own volkstaat?

He was beaten to death last week, allegedly by two black farmworkers. The murder has sparked fears of renewed racial violence in South Africa. But the motive was apparently personal: unpaid wages and, one imagines, a less than agreeable management style.