內(nèi)臟美食:重口味的誘惑

US food author M.F.K. Fisher once wrote about humans, "First we eat, then we do everything else."

美國(guó)美食作家M·F·K·費(fèi)希爾曾如此描寫人類:“先吃飽了飯,才能去干別的事。”

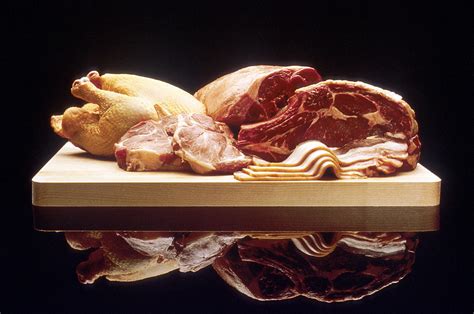

This is why each year we celebrate World Food Day, which falls on Oct 16. But despite the importance of food around the world, food cultures often differ greatly from country to country. For example, things like chicken feet, duck heads, and pig brains are commonly eaten in Asia. If you asked most Westerners to try one of these things, though, the very thought would probably be enough to make them give up meat altogether.

這便是每年10月16日我們都會(huì)慶祝世界糧食日的原因。盡管食物在全球各地都至關(guān)重要,但國(guó)與國(guó)之間的飲食文化卻大相徑庭。比如,雞爪、鴨頭、豬腦等食物在亞洲很常見(jiàn)。但如果你要讓大多數(shù)西方人嘗試一下,估計(jì)他們一想到此,就足以改吃素食了。

At the same time, however, the majority of people in Western nations regard themselves as meat eaters. So, what could be the reason behind this double standard?

但與此同時(shí),西方國(guó)家的大多數(shù)人都認(rèn)為自己是肉食主義者。那么,是什么導(dǎo)致了這樣的不同呢?

There are a number of possible answers to that question, yet one major reason could lie in recent cultural changes. During the mid 20th century and the years following it, eating most parts of an animal was common in many Western countries such as the UK – perhaps owing to rationing as a result of World War II (1939-1945).

這個(gè)問(wèn)題或許有多種答案,但其中的一大原因或許是近代的文化變遷。在20世紀(jì)中期以及接下來(lái)的數(shù)年間,食用動(dòng)物身體的大多數(shù)部位在英國(guó)等西方國(guó)家十分常見(jiàn) ——這或許與二戰(zhàn)期間的定量配給政策有關(guān)。

But later, during the 1960s and 70s, following the introduction of highways in the US and the UK, the popularity of supermarkets in those countries increased, wrote Francesco Burnett, author of Cultural History of Meat: 1900-The Present.

但后來(lái),在上世紀(jì)60-70年代,隨著英美等國(guó)建起了高速公路,超市在這些國(guó)家也普及開(kāi)了,《肉類文化史:1900年至今》一書的作者弗朗西斯科·伯內(nèi)特如此寫道。

Thanks to the popularity and convenience of supermarkets, which tend not to sell animal parts such as the head or limbs, the public's attitude of meat soon shifted. "The 'animal' gradually disappeared from meat, and people's ignorance about what animal the meat they ate came from increased," Burnett added.

由于超市的普及和便利,很少售賣動(dòng)物部位,如頭、四肢等等,公眾對(duì)于肉的態(tài)度很快也發(fā)生了變化。“‘動(dòng)物'的概念慢慢地從“肉類”一詞中消失了,人們開(kāi)始日益忽略他們所吃的肉是哪些動(dòng)物的,”伯內(nèi)特補(bǔ)充道。

As a result, it's believed that many Western cultures slowly began to view meat as simply a food product, rather than as something that came from an animal.

因而人們認(rèn)為,許多西方文化漸漸地只是將肉類視為一種食品,而非動(dòng)物的一部分。

However, this theory may go even further back if we look at the words the English language uses to describe meat. "We 'de-animalize' certain foods that we eat by giving them different names," Hal Herzog, author of Why It's So Hard To Think Straight About Animals, told online magazine Grist. "We don't say it's cooked pig; we say it's pork. And we don't say hamburger is made of cow; we say it's made of beef."

但這種說(shuō)法或許還能追溯回更早的時(shí)間,看看英文中用于形容肉類的詞匯就知道了,“我們給一些食物起了不同的名字,消除了這些食物與動(dòng)物的聯(lián)系,”《為什么很難想到動(dòng)物》一書的作者哈爾·赫爾佐格在接受線上雜志《Grist》采訪時(shí)如此說(shuō)道。“我們不會(huì)說(shuō)煮熟的豬,而是說(shuō)豬肉。我們不會(huì)說(shuō)漢堡包由牛制成,而是說(shuō)由牛肉制成。”

So it seems that there's not one simple answer to this question. When it comes to eating meat, however, perhaps we should simply just enjoy the taste.

所以,這個(gè)問(wèn)題似乎沒(méi)有一個(gè)簡(jiǎn)單的答案。而吃肉時(shí),或許我們只需享受美味即可。