No matter how seldom you've opened that calculus textbook on your shelf, the chances of worms having eaten it are pretty low. But books written back in the Renaissance have had much better odds of becoming worm food. Now we know that the holes left by worms as they dine can be used as data. A study in the journal Biology Letters explains how.

即使你很久沒(méi)翻過(guò)書架上的那本算術(shù)教材了,但它被蠕蟲啃食的幾率還是相當(dāng)?shù)偷摹H欢鴮懹谖乃噺?fù)興時(shí)期的書被蠕蟲啃食的幾率更大。據(jù)了解蠕蟲啃食后留下的破洞能被用作研究數(shù)據(jù)。刊登在《生物學(xué)快報(bào)》的一項(xiàng)報(bào)告會(huì)解釋其中原由。

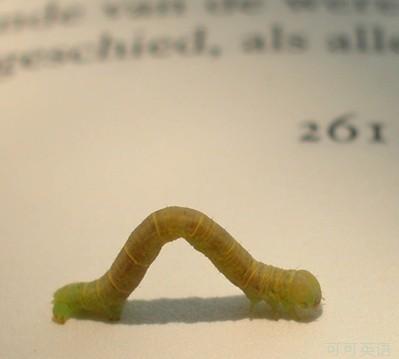

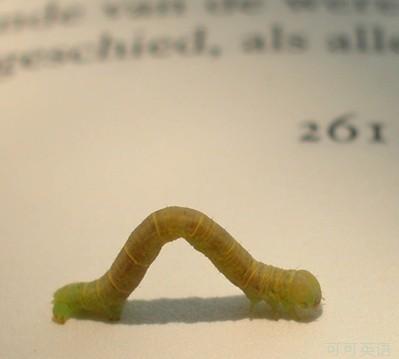

Researchers measured more than 3,000 wormholes in books and artwork created between 1462 to 1899. Based on hole size, they figured out that there were two main culprits: larvae of the Common Furniture Beetle and the Mediterranean Furniture Beetle.

研究人員測(cè)量了三千多個(gè)蟲洞,這些蟲洞分布在1462年至1899年之間出版的書和藝術(shù)品上。基于蟲洞的尺寸,研究人員找出了兩大“書蟲”:普通家具甲蟲的幼蟲以及地中海家居甲蟲的幼蟲。

Today both of those beetles are found all over Europe. But during the Renaissance the two beetle species were geographically isolated. It wasn't until we started shipping furniture that they crossed that divide.

現(xiàn)在,這兩種甲蟲遍布于歐洲大陸。但在文藝復(fù)興時(shí)期,這兩種甲蟲在地理上相互隔離。直到人們開始用船運(yùn)輸家具,這兩個(gè)物種才跨越了地界。

Museums today keep insects away from their precious specimens. So researchers may be able to use the sizes of the wormholes in items of uncertain origin to identify their larval attackers. Which then offers clues about the item’s geographical history. Really gives a new meaning to the phrase “book worm.”

如今為保護(hù)珍貴的標(biāo)本,博物館要使它們遠(yuǎn)離昆蟲。因此對(duì)于來(lái)源不確定的標(biāo)本,研究人員可以通過(guò)它的蟲洞尺寸來(lái)辨別的幼蟲攻擊者。這樣也為標(biāo)本的地理歷史提供了線索。這賦予短語(yǔ)“書蟲”一個(gè)全新的含義。

原文譯文屬可可原創(chuàng),未經(jīng)允許請(qǐng)勿轉(zhuǎn)載!

來(lái)源:可可英語(yǔ) http://www.ccdyzl.cn/broadcast/201211/211302.shtml