In the summer of 1977, New York City was burning.

1977年的夏天,紐約市在燃燒。

A 25-hour blackout, triggered by lightning striking key transmission lines, led to widespread looting, riots, and more than a thousand fires.

由閃電擊中關鍵輸電線路引發的25小時大停電,引發了大范圍的搶劫、騷亂和一千多起火災。

That night alone, the fire department battled blazes across Harlem, Brooklyn, and the South Bronx, a shocking surge in a city already averaging four dozen fires a day. New York City was at an all time low.

僅在那天晚上,消防部門便在哈萊姆區、布魯克林區和南布朗克斯區奮力撲救各處火情,而這座平日里日均火災數量就已多達48起的城市,當晚火災數量的激增更是令人觸目驚心。此時的紐約市正墜入歷史的最低谷。

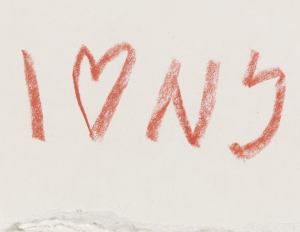

But what saved the city wasn't a bailout or sweeping reform. It was a simple sketch—drawn in the back of a yellow cab by designer Milton Glaser.

但真正拯救這座城市的不是救助或全面改革。而是設計師米爾頓·格拉澤在一輛黃色出租車的后座上勾勒的一幅簡單草圖。

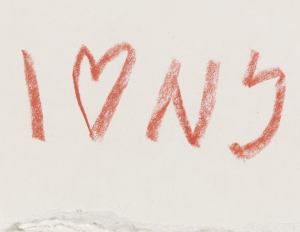

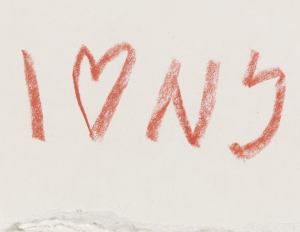

His now-iconic "I Love New York" logo became a rallying cry, a symbol of pride at a time when the city was desperate to believe in itself again.

他創作的、現在已經是標志性的“我愛紐約”標志,成為了一個戰斗口號,并在這個城市迫切希望重拾自信的時候,成為了一個驕傲的象征。

"It was the perfect storm of need and meaning coming together," says Steven Heller, a design historian and former New York Times art director who has chronicled the logo's cultural legacy.

設計歷史學家、曾擔任《紐約時報》藝術總監,并記錄下該標志文化遺產的史蒂文·海勒說道:“這是需求與意義完美交融的一場風暴。”

New York's decline didn't happen overnight. First, the factories closed, causing 300,000 manufacturing jobs to vanish in just six years.

紐約的衰落并非一朝一夕之事。起初,工廠紛紛關閉,短短六年時間,30萬個制造業崗位消失得無影無蹤。

Wealthy residents fled to the suburbs, taking with them their tax dollars. The city started borrowing money to make payroll.

富裕的居民帶著資金搬離城市,前往郊區定居。這座城市的稅收也隨之銳減。

Then came the budget cuts. Teachers got pink slips. Sanitation trucks sat idle as garbage rotted on street corners.

緊接著的是預算削減。教師們被解雇了。垃圾在街角腐爛,環衛車被迫閑置。

"The city was closing fire departments because it didn't have the money to maintain them," says Ryan Purcell, a history professor at Sarah Lawrence College and the creator of the Soundscapes NYC podcast. "They chose which neighborhoods to abandon."

莎拉勞倫斯學院歷史教授、“紐約之聲”播客創始人瑞安·珀塞爾表示:“由于缺乏資金維持運營,城市不得不關閉部分消防部門。它們主動選擇放棄一些社區。”

Crime spiked to more than a thousand murders annually, and arson became a business model.

犯罪率飆升至每年一千多起謀殺案,縱火竟成為一種牟利模式。

"Landlords were burning their buildings to collect insurance," says Purcell. "It was more profitable than collecting rent."

珀塞爾指出:“房東為了騙取保險金,故意縱火燒毀自己的建筑,因為這樣比收租獲利更多。”

The South Bronx lost more than 97 percent of its buildings on some blocks to flames and abandonment.

在南布朗克,部分街區97%以上的建筑因火災或遭遺棄而損毀。

It became the epicenter for what officials coldly called "planned shrinkage," a controversial urban planning strategy that pulled services from poor neighborhoods to force depopulation.

這里成為了所謂“有計劃收縮”政策的核心區域,這一頗具爭議的城市規劃策略,通過減少對貧困社區的服務投入,迫使居民外遷。

By 1975, police handed visitors pamphlets titled "Welcome to Fear City," at every entry point to Manhattan -- Grand Central, Penn Station, Port Authority -- warning tourists to stay away until things change.

到了1975年,在曼哈頓的各個入口,如中央車站、賓夕法尼亞車站、港務局,警方都會向游客發放名為《歡迎來到恐懼之城》的宣傳手冊,警示游客在情況改善前切勿前往。

Subway cars were coated in graffiti and plagued by breakdowns.

地鐵車廂上滿是涂鴉,故障頻繁發生。

When the city begged Washington for help, the Daily News captured President Ford's infamous response: FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD.

當紐約市向華盛頓尋求援助時,《每日新聞》報道了福特總統那句臭名昭著的回應:“福特對紐約市說:去死吧。”

"If 'I Love New York' came about and nobody felt that New York was worth saving, it might not have worked," says Heller. "But people loved New York and wanted it to be a better place."

海勒表示:“如果在‘我愛紐約’標志誕生之時,人們都覺得這座城市無藥可救,那么它或許根本無法發揮作用。但實際上,大家熱愛著紐約,想讓這里變得更好。”