Even we can tolerate it only up to a point. The oxygen level in our cells is only about a tenth the level found in the atmosphere.

連我們對氧的耐受力也是有限度的。我們細胞里的氧氣濃度,只有大氣里的大約十分之一。

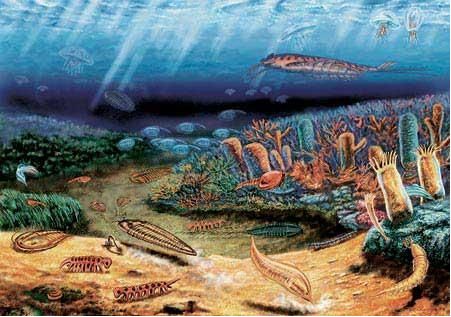

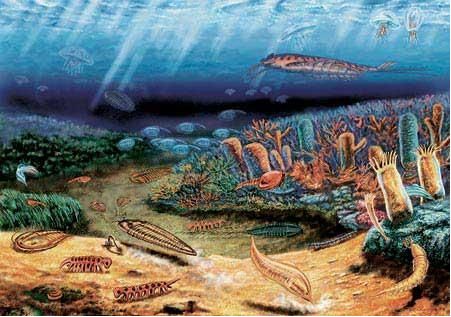

The new oxygen-using organisms had two advantages. Oxygen was a more efficient way to produce energy, and it vanquished competitor organisms. Some retreated into the oozy, anaerobic world of bogs and lake bottoms. Others did likewise but then later (much later) migrated to the digestive tracts of beings like you and me. Quite a number of these primeval entities are alive inside your body right now, helping to digest your food, but abhorring even the tiniest hint of O2. Untold numbers of others failed to adapt and died.

新的會利用氧的細菌有兩個優(yōu)勢。氧能提高產(chǎn)生能量的效力,它打垮了與之競爭地微生物。有的撤退到厭氧而泥濘的沼澤和湖底世界里;有的也照此辦理,但后來(很久以后)又移居到了你和我這樣的有消化力地地方。有相當(dāng)數(shù)量的這類原始實體此時此刻就生活在你的體內(nèi),幫助消化你的食物,但厭惡哪怕是一丁點兒氧氣。還有無數(shù)的其他細菌沒有適應(yīng)能力,最后死亡了。

The cyanobacteria were a runaway success. At first, the extra oxygen they produced didn't accumulate in the atmosphere, but combined with iron to form ferric oxides, which sank to the bottom of primitive seas. For millions of years, the world literally rusted—a phenomenon vividly recorded in the banded iron deposits that provide so much of the world's iron ore today. For many tens of millions of years not a great deal more than this happened. If you went back to that early Proterozoic world you wouldn't find many signs of promise for Earth's future life. Perhaps here and there in sheltered pools you'd encounter a film of living scum or a coating of glossy greens and browns on shoreline rocks, but otherwise life remained invisible.

藻青菌逃跑并取得了成功。起初,它們所產(chǎn)生的額外的氧沒有積聚在大氣里,而是與鐵化合,成為氧化鐵,沉入了原始的海底。有幾百萬年的時間,世界真的生銹了——這個現(xiàn)象由條形鐵礦生動地記錄了下來,今天卻為世界提供了那么多的鐵礦石。在幾千萬年時間里,發(fā)生的情況比這多不了多少。要是你回到那個元古代初期的世界,你發(fā)現(xiàn)不了很多跡象,說明地球上未來的生命是很有前途的。也許,你在這里和平那里隱蔽的水塘里會遇上薄薄的一層有生命的浮渣,或者在海邊的巖石上會看到一層亮閃閃的綠色和裼色的東西,但除此之外生命依然毫無蹤影。

來源:可可英語 http://www.ccdyzl.cn/Article/201807/557230.shtml