文藝版塊

Book review

書評

Craft and commerce

手工業(yè)和商業(yè)

Shifting plates

不斷變化的盤子

Porcelain: A History from the Heart of Europe.

瓷器:歐洲中心的歷史

By Suzanne Marchand.

作者:蘇珊娜·馬錢德。

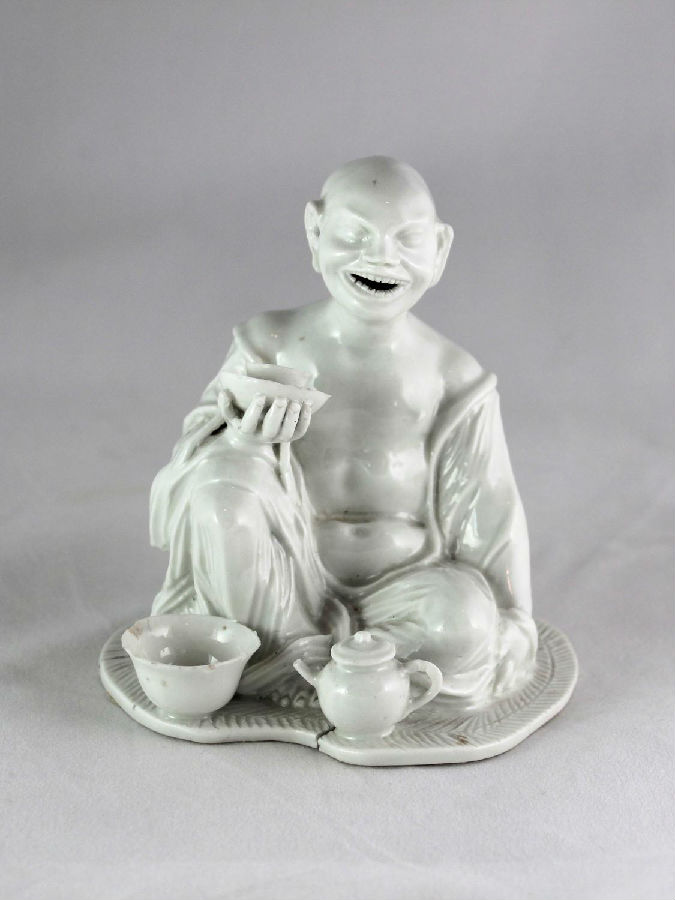

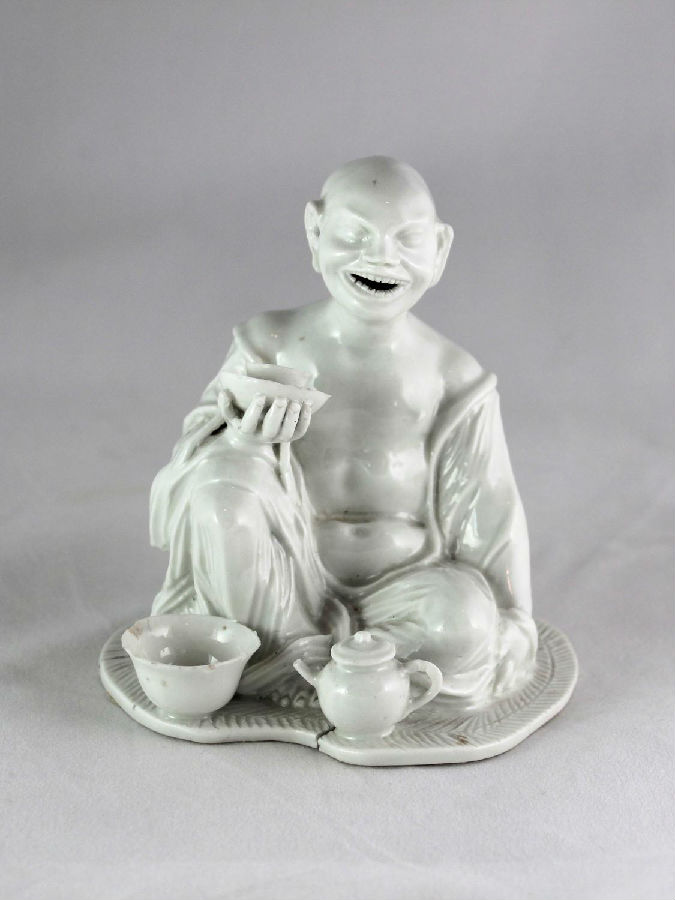

It sounds like a fairy-tale.A visionary alchemist, arrested by a tyrannical ruler, is put to work turning scraps into riches. Yet for a few years in the early 18th century Johann Friedrich Bottger was a genuine Rumpelstiltskin. Seized by Augustus the Strong, elector of Saxony, after he crossed Prussia’s frontier, Bottger was imprisoned and ordered to conjure up treasure—and, in a sense, he did. He didn’t make gold, but Bottger was the first European to create something almost as precious: porcelain.

這聽起來像個(gè)童話故事。暴君逮捕了一名有創(chuàng)見的煉金術(shù)士,并派他去變廢為寶。在18世紀(jì)初,約翰·弗雷德里克·博特格還是個(gè)真正的少年。博特格在穿過普魯士邊界后,被薩克森選帝侯“強(qiáng)者”奧古斯圖斯抓住囚禁了起來,并被命令創(chuàng)造出寶藏,而從某種意義上來說,他做到了。博特格沒有制造黃金,但他是第一個(gè)創(chuàng)造了與黃金幾乎同等珍貴的瓷器的歐洲人。

As Suzanne Marchand shows in her meticulous new book, porcelain has been integral to German life since its reinvention in Saxony in 1708 (the Chinese perfected the craft centuries earlier). It was initially a plaything for princes, as Bottger’s incarceration suggests; Augustus and his rivals sponsored state-run factories for what one called the “splendour and prestige” of their realms.From that beginning, Ms Marchand traces porcelain’s role in German history, examining its uses from Romantic busts of Goethe to Nazi egg cups.

就像是蘇珊娜·馬錢德在她精心完成的新書中展示的那樣,自從1708年博特格在薩克森州重新發(fā)明了瓷器(幾個(gè)世紀(jì)前中國人完善了這一工藝),瓷器就一直是德國人生活中不可或缺的一部分。瓷器最初是王子們的玩物,博特格受到囚禁也表明了這一點(diǎn);奧古斯圖斯和他的對手贊助了國營工廠,以獲得所謂的王國“輝煌和威望”。從那一刻起,馬爾漢德女士追溯了瓷器在德國歷史上的作用,從歌德的浪漫半身像到納粹蛋杯,她考察了瓷器的用途。

“Porcelain” is about more than culture. Because the commodity was prized and produced over centuries, the author uses it to explore wider economic changes. Ultimately it became thoroughly industrialised— porcelain’s use in false teeth and telegraph insulator tubes leads Ms Marchand to call it the plastic of its day—but the path to modernity meandered. Several early factories, including the famous one at Meissen, were just converted palaces or monasteries, run by courtiers in powdered wigs. Some idiosyncrasies survived into the 20th century: though they hated all things aristocratic, East German officials brought back classic rococo figurines after Marxist alternatives proved unsellable.

“瓷器”不僅僅是文化。由于幾個(gè)世紀(jì)以來這種商品一直受到高度重視和生產(chǎn),因此作者用它來探索更廣泛的經(jīng)濟(jì)變化。最終,它徹底工業(yè)化了——將瓷器應(yīng)用于假牙和電線絕緣管中,使馬錢德女士將其稱之為當(dāng)時(shí)的塑料——但通往現(xiàn)代化的道路是曲折的。早期的幾家工廠,包括著名的梅森工廠,都是由宮殿或修道院改建的,由頭戴撲粉假發(fā)的朝臣經(jīng)營著。一些特質(zhì)延續(xù)到了20世紀(jì):盡管他們痛恨一切貴族化的東西,但在馬克思主義的替代品被證明無法出售后,東德官員恢復(fù)生產(chǎn)經(jīng)典的洛可可雕像。

譯文由可可原創(chuàng),僅供學(xué)習(xí)交流使用,未經(jīng)許可請勿轉(zhuǎn)載。