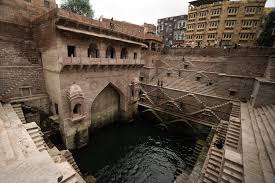

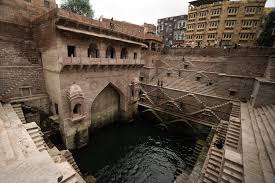

India has thousands of surviving stepwells, but the great majority are similarly run-down. Many others have vanished, often filled in and built upon. This neglectful attitude is extraordinary, for they are one of India’s unsung wonders. At last, through restoration efforts by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC), among others, they are starting to get the recognition they deserve.

印度有數千口現存的梯級井,但絕大多數梯級井也同樣在衰竭。許多已經消失,經常需要填補和重修。這種忽視的態度是不同尋常的,因為梯級井是印度無名的奇跡之一。最后,通過阿加汗文化信托基金等機構的修復努力,梯級井開始得到應有的承認。

The earliest of the wells date back almost 2,000 years. They were first and foremost a response to a climate in which a year’s rains fall chiefly in the four brief months of the summer monsoon, when they fall at all. The point of the staircases and side ledges is to provide permanent access to ever-fluctuating water levels—and cool shelter in the hottest months. In the north-western regions that are India’s most arid, such as Rajasthan and Gujarat, the baolis underwrote life, as sources of both irrigation and drinking water. They were often located on ancient trade routes. In Delhi, every community once had its own tank.

最早的梯級井可以追溯到2000年前。梯級井首先是對一種氣候的反應,在這種氣候中,一年的降雨主要集中在夏季季風的四個月里,而這四個月正是雨季來臨的時候。樓梯和側壁架的重點是為不斷波動的水位提供永久性的通道,并在最熱的月份提供涼爽的庇護所。在印度最干旱的西北地區,如拉賈斯坦邦和古吉拉特邦,baoli作為灌溉和飲用水的來源,支撐了人們的生活。它們通常坐落在古老的貿易路線上。在德里,每個社區曾經都有自己的水槽。

Many stepwells were used for ablution; the tanks associated with mosques, Hindu temples and other shrines offered the most purificatory form. Summoning water from the depths was also a symbol of temporal power. Around Hyderabad in south-central India, many of the baolis were built by kings and zamindars. A surprising number were built at the behest of women, including princesses, courtesans and merchants’ wives, who wished to attain immortality through the gift of water. Indeed, stepwells have always been considered women’s spaces—places to gather without inhibitions, away from men’s domineering eyes (in India, after all, it is traditionally a woman’s job to fetch and carry water). Rani-ki- Vav, or the queen’s stepwell, in Patan in Gujarat, graces the new 100-rupee note.

許多階梯井用于洗浴;清真寺、印度寺廟和其他神殿的水槽提供了最潔凈的方式。從深處召喚水也是世俗力量的象征。在印度中南部的海德拉巴周圍,許多寶麗寺是由國王和贊美達建造的。在女性的要求下,包括公主、交際花和商人的妻子,她們希望通過水的禮物獲得永生,因此建造了數量驚人的雕像。事實上,階梯井一直被認為是女性的空間——一個不受約束、遠離男性霸道目光的地方(畢竟,在印度,傳統上取水和挑水是女性的工作)。古吉拉特邦帕坦的“女王階梯井”為新版面值100的盧比增色。

譯文由可可原創,僅供學習交流使用,未經許可請勿轉載。