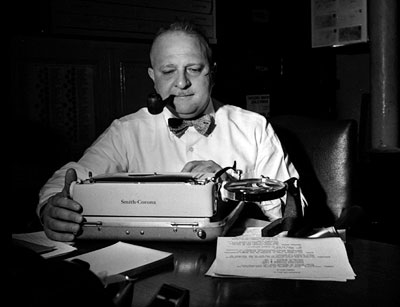

Martin Tytell, a man who loved typewriters, died on September 11th, aged 94

馬丁•泰特爾,一位與打字機相愛的人,逝于9月11日,享年94歲

ANYONE who had dealings with manual typewriters-the past tense, sadly, is necessary-knew that they were not mere machines. Eased heavily from the box, they would sit on the desk with an air of expectancy, like a concert grand once the lid is raised. On older models the keys, metal-rimmed with white inlay, invited the user to play forceful concertos on them, while the silvery type-bars rose and fell chittering and whispering from their beds. Such sounds once filled the offices of the world, and Martin Tytell’s life.

任何曾與手動打字機打過交道的人(很遺憾用了”曾”字,但這是必要的)都知道打字機不只是機器,他們悄然離開箱子,帶著期待著神氣坐在桌子上,就像一架架剛打開蓋子的平臺大鋼琴。白體鑲黑邊的老款打字機的鍵盤向使用者發出邀請,請他們演奏強有力的協奏曲,同時銀色的打印桿一升一降,嗒嗒作響。這種聲音曾在世界各地的辦公室里回蕩,也貫穿了泰特爾的一生。

Everything about a manual was sensual and tactile, from the careful placing of paper round the platen (which might be plump and soft or hard and dry, and was, Mr Tytell said, a typewriter’s heart) to the clicking whirr of the winding knob, the slight high conferred by a new, wet, Mylar ribbon and the feeding of it, with inkier and inkier fingers, through the twin black guides by the spool. Typewriters asked for effort and energy. They repaid it, on a good day, with the triumphant repeated ping! of the carriage return and the blithe sweep of the lever that inched the paper upwards.

手動的裝置意味著感官上的喜悅,有細心地把紙裝進壓紙卷筒(有的又松又軟,有的又硬又干,用泰特爾的話說,壓紙卷筒是打字機的心臟),有緊手輪的嗡嗡聲,有新裝的美拉色帶及其油墨通過色帶卷軸的兩個黑色指示標記進行略帶高亢的交談。打字機要你精力十足。心情好時他們會報償你,用連貫的回車聲進行回報,用輕快的轉桿進行回報,轉桿會把紙寸寸推進。

Typewriters knew things. Long before the word-processor actually stored information, many writers felt that their Remingtons, or Smith-Coronas, or Adlers contained the sum of their knowledge of eastern Europe, or the plot of their novel. A typewriter was a friend and collaborator whose sickness was catastrophe. To Mr Tytell, their last and most famous doctor and psychiatrist, typewriters also confessed their own histories. A notice on his door offered “Psychoanalysis for your typewriter, whether it’s frustrated, inhibited, schizoid, or what have you,” and he was as good as his word. He could draw from them, after a brief while of blue-eyed peering with screwdriver in hand, when they had left the factory, how they had been treated and with exactly what pressure their owner had hit the keys. He talked to them; and as, in his white coat, he visited the patients that lay in various states of dismemberment on the benches of his chock-full upstairs shop on Fulton Street, in Lower Manhattan, he was sure they chattered back.

打字機洞悉事態。早在文字處理器能存儲信息之前,許多作家都感覺到他們的Remingtons、Smith-Coronas或Adlers打字機內存有他們關于東歐的知識,存有他們小說的情節。打字機是朋友,又是伙伴,他要是生病了將是一場巨大的災難。泰特爾是打字機最后一個也是最富盛名的內外科及精神病醫生,他們向泰特爾何傾述各自的人生。泰特爾的門上貼有一則通知”為閣下的打字機進行心理分析,分析他是否沮喪、抑郁亦或精神分裂”。這可不是吹牛。泰特爾只要拿著螺絲刀用他的藍眼睛對一臺打字機看上一小會兒,他就能知道這臺機器的出廠時間,隨后的境遇,以及他的主人敲打鍵盤力度的大小。當泰特爾身著白大褂,在其滿滿當當的樓上店鋪里(位于曼哈頓福通大街)探訪那些被不同程度肢解的”病人”時,他與打字機聊著天,并確信這些打字機也在同他交談。