But, someone might argue, that's natural beauty.

但有人也許會爭辯,那是自然美。

How about artistic beauty? Isn't that exhaustively cultural?

藝術(shù)的美又如何呢?那難道不是純粹的文化影響嗎?

No, I don't think it is. And once again, I'd like to look back to prehistory to say something about it.

不,我不這么認(rèn)為。再次,我們回到史前,聊聊史前的一些事。

It is widely assumed that the earliest human artworks are the stupendously skillful cave paintings that we all know from Lascaux and Chauvet.

普遍認(rèn)為,最早的人類藝術(shù)品是極富技巧的洞穴畫,我們都知道從拉斯科洞窟到蕭韋洞窟。

Chauvet caves are about 32,000 years old, along with a few small, realistic sculptures of women and animals from the same period.

蕭韋洞窟大約有3萬2千年的歷史,其中還有同一時期的一些小的、寫實的婦女和動物的雕像。

But artistic and decorative skills are actually much older than that.

但藝術(shù)和裝飾技巧的存在實際上要更早些。

Beautiful shell necklaces that look like something you'd see at an arts and crafts fair,

漂亮的貝殼項鏈,看起來就像是藝術(shù)品和手工藝品,

as well as ochre body paint, have been found from around 100,000 years ago.

還有赭色的人體繪畫,遠(yuǎn)在10萬年前就存在了。

But the most intriguing prehistoric artifacts are older even than this.

但最酷的史前人工制品比這些還要早。

I have in mind the so-called Acheulian hand axes.

我印象中是被稱為阿舍利手斧的手工制品。

The oldest stone tools are choppers from the Olduvai Gorge in East Africa.

最古老的石制工具是在東非的奧杜威峽谷發(fā)現(xiàn)的石斧。

They go back about two-and-a-half-million years.

它的歷史要追溯到兩百五十萬年前。

These crude tools were around for thousands of centuries,

這類粗糙的工具存在了數(shù)千個世紀(jì),

until around 1.4 million years ago when Homo erectus started shaping single, thin stone blades,

直到大約一百四十萬年前,直立人開始打磨單個的薄石刀片,

sometimes rounded ovals, but often in what are to our eyes an arresting, symmetrical pointed leaf or teardrop form.

有時是橢圓形的,但通常,在我們眼中,是醒目的對稱的尖葉子形或淚滴形。

These Acheulian hand axes -- they're named after St. Acheul in France, where finds were made in 19th century

這些阿舍利手斧--名稱取自法國的圣阿舍爾,這些手斧是十九世紀(jì)在那兒發(fā)現(xiàn)的

have been unearthed in their thousands, scattered across Asia, Europe and Africa,

出土了數(shù)千件,散布在亞洲、歐洲和非洲,

almost everywhere Homo erectus and Homo ergaster roamed.

幾乎遍布每一處直立人或者匠人到過的地方。

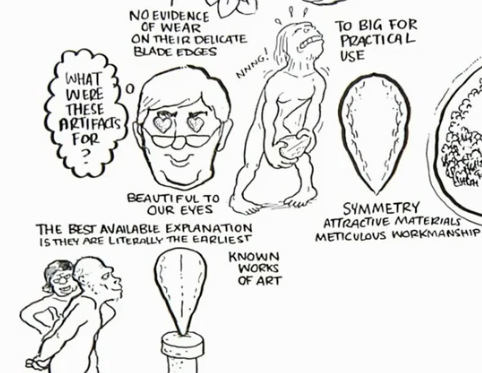

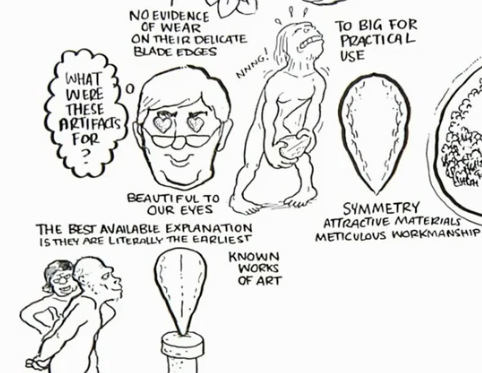

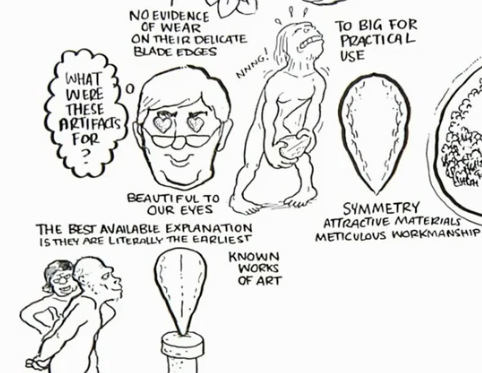

Now, the sheer numbers of these hand axes shows that they can't have been made for butchering animals.

這些手斧眾多的數(shù)量表明它們不是用于屠宰動物。

And the plot really thickens when you realize that, unlike other pleistocene tools,

更復(fù)雜的是當(dāng)你考慮到,不像其他更新世的工具,

the hand axes often exhibit no evidence of wear on their delicate blade edges.

在這些手斧精美脆弱的刀刃邊緣找不到任何磨損的痕跡。

And some, in any event, are too big to use for butchery.

而且它們中的一些,無論用在屠宰什么動物上,都太大了點。

Their symmetry, their attractive materials and, above all,

它們的對稱性和引人注意的材料,還有,尤其是,

their meticulous workmanship are simply quite beautiful to our eyes, even today.

它們那精細(xì)的做工對我們來說非常美麗,即使在今天也是如此。