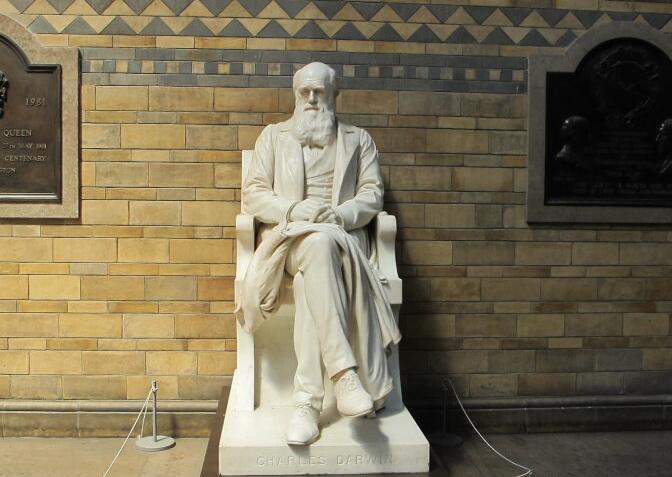

Still, his altruism in general toward his fellow man did not deflect him from more personal rivalries. One of his last official acts was to lobby against a proposal to erect a statue in memory of Charles Darwin. In this he failed—though he did achieve a certain belated, inadvertent triumph. Today his statue commands a masterly view from the staircase of the main hall in the Natural History Museum, while Darwin and T. H. Huxley are consigned somewhat obscurely to the museum coffee shop, where they stare gravely over people snacking on cups of tea and jam doughnuts.

不過,他對人類的無私精神并沒有使他忘記自己的對手。他最后一個正式舉動是到處游說,反對一項關于修建紀念查爾斯·達爾文的雕像的建議。他的這次努力沒有成功——雖然他無意之中為自己贏得了一個勝利,只是晚了一些。今天,他自己的雕像從自然史博物館大廳的樓梯上像主人般地俯瞰著下面,而達爾文和赫胥黎的雕像卻不大顯著地放在博物館的咖啡店里,以嚴肅的目光凝視著人們喝茶,吃果醬炸面包圈。

It would be reasonable to suppose that Richard Owen's petty rivalries marked the low point of nineteenth-century paleontology, but in fact worse was to come, this time from overseas. In America in the closing decades of the century there arose a rivalry even more spectacularly venomous, if not quite as destructive. It was between two strange and ruthless men, Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh.

有理由認為,理查德·歐文那心胸狹窄的對抗行為,標志著19世紀的地質學進入低谷,但更嚴重的對抗即又發生,這一次來自海外。在那個世紀的最后幾十年里,美國也發生了一次對抗,其程度要惡毒得多,盡管破壞力沒有那么大。這場對抗發生在兩個古怪而又冷酷的人之間:愛德華·德林克·柯普和奧斯尼爾·查爾斯·馬什。

They had much in common. Both were spoiled, driven, self-centered, quarrelsome, jealous, mistrustful, and ever unhappy. Between them they changed the world of paleontology.

他們有許多共同之處。兩個人都已被寵壞,有緊迫感,以自我為中心,動輒吵架,妒忌心強,不信任別人,老是郁郁不樂。他倆一起改變了古生物學界。