I used, oddly enough, to get lots of letters-in the almost decade I ran The Times obituaries-saying,Oh, I do not seem to be getting any younger, and I thought it might be helpful to let you have a few notes on my life'. And they were unbelievable. People's self conceit-saying things like, 'Though a man of unusual charm, and this kind of thing. I mean, I couldn't believe that people would write this about themselves. So of course no-one nowadays self-commissions their own obituary, and those that were sent in always ended up straight in the waste-paper basket.

我收到過不少寫著我已時日無多,想來有必要讓你們了解一下我的生平事跡的信。它們簡直讓人難以置信,字里行間透出的盡是狂妄自大.充斥著類似雖然他是一個極具魅力的人的描述。我很難相信有人會如此評價自己。當然,如今沒有誰委托別人為自己寫訃告,早年間的這種倌通常也直接進了廢紙簍。

"I used to rather boast, and say that on the obits page of 'The Times', 'We are writing the first version of history of our generation'. And that is what I think it ought to be. It certainly isn't for the relatives, or the family, or even the friends."

我以前總是為《泰晤士報》的訃聞版夸口說“我們在書寫當代歷史的第一個版本。這也正是訃告的價值所在。它自然并非寫給逝者的家人或朋友看的。

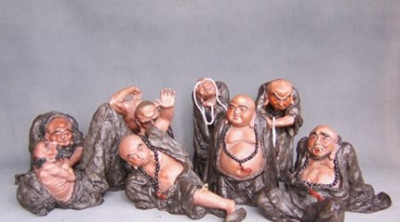

The Tang obituaries were not for family and friends, either. But nor were they the first version of history for their generation. The intended audience for the obituary of Liu Tingxun was not earthly readers, but the judges of the underworld, who would recognise his rank and his abilities, and award him the prestigious place among the dead that was his due.

唐朝的訃聞也同樣不是寫給家人或朋友的,但它們亦非那一代歷史的首個版本。劉廷茍的訃聞的目標讀者并非在世的人,而是陰間的判官,它讓他們得以了解他的地位和能力,好在陰間給予他相應的地位。