Asia

亞洲

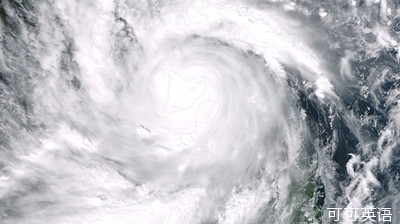

Cyclones and climate change

颶風與氣候變化

The new normal?

習以為常?

Physics suggests that storms will get worse as the planet warms. But it is too early to tell if it is actually happening

物理學研究表明全球變暖將導致更猛烈的風暴,但一切尚未可知

WAS typhoon Haiyan the strongest recorded storm to make landfall?

臺風海燕是有記錄以來的最強登陸風暴嗎?

Meteorologists will never know. Reliable records go back only a few decades.

Meteorologists will never know. Reliable records go back only a few decades.

氣象學家們恐怕永遠都不會知道。可靠記錄只能回溯幾十年。

But it is surely one of them. Besides the devastation and the death toll, one way to assess its potency is to compare it with Katrina, the hurricane that devastated New Orleans in 2005.

不過可以肯定,這是史上最強風暴之一。除了統(tǒng)計摧毀的建筑和死亡的人數(shù),評估該風暴威力的另一個辦法,是將它和2005年摧毀新奧良的卡特里娜颶風作比較。

At its most intense, Haiyan's peak wind speeds were probably greater than 300kph.

在高峰期,海燕的最高風速可能超過每小時300公里,

The best estimate for Katrina, when it hit land, is around 200kph.

而卡特里娜登陸時,其風速估計在每小時200公里左右。

Regardless of its precise position in the historical hierarchy, Haiyan—like Katrina—has provoked discussion about the effects of global warming on tropical storms.

且不考慮臺風海燕在歷史上排行第幾,海燕—如同卡特里娜—已激起關于全球變暖對熱帶風暴影響的討論。

Naderev Sano, the Philippines' representative at a climate summit in Warsaw, was unequivocal, daring doubters to visit his homeland.

在華沙舉行的聯(lián)合國氣候變化大會上,菲律賓代表Naderev Sano態(tài)度堅定,他請全球變暖效應的懷疑者們去他的祖國看一看,

The trend we now see is that more destructive storms will be the new norm, he said.

并說:我們從眼下的趨勢可以看到,更具破壞性的風暴將成為常態(tài)。

In theory, a warmer world should indeed produce more potent cyclones.

理論上,全球變暖確實將引發(fā)更具威力的風暴。

Such storms are fuelled by evaporation from the ocean.

這類風暴來自海洋的水氣蒸騰。

Warmer water means faster evaporation, which means more energy to power the storm.

水溫越高,蒸發(fā)越快,這意味著暴風將來得更猛烈。

A warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, which means more rain.

而溫暖的大氣將儲存更多水分,這將造成更多的降雨。

But other factors complicate things.

不過其他一些因素使事情變得復雜。

Tropical cyclones cannot form when wind speeds in the upper and lower atmosphere differ too much.

當高層和底層大氣的風速相差懸殊時,熱帶氣旋便無法形成。

Climate models suggest, in the North Atlantic at least, that such divergent winds may be more common in a warmer world.

氣候模型表明,至少在北大西洋,如果氣溫升高,那這類風速甚異的氣流可能會變得更常見。

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reckons that the frequency of cyclones will stay the same or decrease while their average intensity goes up.

政府間氣候變化專門委員會估計,當颶風的平均強度增加時,它的頻率或許會保持不變甚至降低。

That is the forecast. But the evidence so far is messy.

這些都只是預測。可迄今為止的證據相當混亂。

Meteorological records are of uneven quality, and tropical storms vary widely in intensity, which makes spotting trends tricky.

氣象記錄的質量良莠不齊,熱帶風暴的強度變化不定,這使得認清趨勢的任務變得棘手。

One potent storm from 1979, Typhoon Tip, holds the record for the lowest atmospheric pressure recorded, another measure of a storm's intensity.

另一項臺風強度的測算顯示,1979年的超級強臺風泰培保持了最低大氣壓的記錄。

Yet levels of carbon dioxide, the main greenhouse gas, were only 337 parts per million in 1979, compared with 394ppm in 2012.

然而,相比2012年的394ppm,主要溫室氣體二氧化碳的濃度在1979年僅為337ppm。

The IPCC concludes that, although there is good evidence for more and stronger Atlantic hurricanes over the past 40 years, there is no consensus on the cause of them.

IPCC推斷,雖然有充分的證據顯示,在過去的40年間,大西洋的颶風正變得更為頻繁和猛烈,但IPCC表示,對于此現(xiàn)象的起因,業(yè)內并未形成共識。

Worldwide, there is no trend in either the frequency or the intensity of tropical storms.

在世界范圍內,關于熱帶風暴發(fā)生的頻率或強度的趨勢依舊無跡可尋。

And, given the rarity of such storms as Typhoon Haiyan, it will take a long time for any trend to become apparent.

不僅如此,由于像臺風海燕這樣的罕見風暴的出現(xiàn),在相當長一段時間內,風暴的趨勢將愈加撲朔迷離。