膽小的新貴

Aristotle believed they were democracy's secret weapon-the protectors of social values,the moderators of political extremism,and believers in a society run by laws instead of by strongmen.

亞里士多德認為,他們是民主體制的秘密武器—他們保衛社會價值觀、緩和政治極端主義、在政府法令面前捍衛理性,并相信社會應當由法律而非鐵腕人物來治理。

They have also been the engines of economic growth,setting the stage centuries ago for the expansion of capitalism and global trade,and continuing through the ages to snap up every new gadget in sight.

同時,他們還是經濟增長的引擎,在幾個世紀前就為資本主義和全球貿易的擴張搭起了舞臺,并且多年來一直都搶先弄到自己所知的一切新潮玩意或服務。

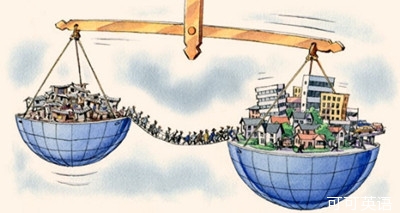

Now, with the Western middle classes sinking into debt and distress,many economists look to a new emerging-market middle class as the potential foundation for a new age of global safety and prosperity.

Now, with the Western middle classes sinking into debt and distress,many economists look to a new emerging-market middle class as the potential foundation for a new age of global safety and prosperity.

如今,隨著西方中產階級深陷債務與危機之中,許多經濟學家都將新興市場的中產階級視作全球安全與繁榮新時代的潛在基礎。

As large developing nations became more prosperous,it was always assumed that they would become more like the suburbs of Washington or London-liberal, democratic,market-friendly bastions not only of Western-style consumerism but also of political liberty.

在大的發展中國家日趨繁榮之時,人們一直以為它們會變得更像是華盛頓或者倫敦的郊區—它們自由、民主、注重市場,是西方消費主義及政治自由的堡壘。

With time and wealth, they would become just like us.

隨著時間的推移與財富的積累,他們會變得與我們一模一樣。

The truth is that they are not becoming just like us.

事實上,他們不會變得與我們一樣。

The global middle class is rising faster than expected,in numbers and in wealth,but converging incomes are not yielding shared values.

全球中產階級在人數與財富方面的增長速度超出了我們的預計。

The emerging bourgeoisie is a patchwork of contradictions:clamorous but rarely confrontational politically,supporters of globalization yet highly nationalistic,proud of their nations' upward mobility yet insecure and fearful they will fall back,fiercely individualistic but reliant on government subsidies,and often socially conservative.

但趨同的收入水平卻未能產生共同的價值觀。新興資產階級是一種矛盾的集合體: 他們大聲發表意見,卻很少參與政治交鋒;支持全球化,卻有高度民族主義傾向;對自己國家不斷上升的勢頭感到自豪,卻缺乏安全感,并擔心自身會出現倒退;極具個人主義,卻依賴政府補助,而且往往是社會保守派。

Many of the aspiring elite seem willing to let the powers that be-whether authoritarian governments or elected ones-call the shots as long as they deliver the spoils of growth.

許多有抱負的精英似乎愿意讓現政權—無論是專制政府還是民選政府—掌控政局,只要它們能帶來經濟增長的好處。

It's also worth remembering that the new middle classes are psychologically driven by an odd mix of pride and insecurity.

同樣要記住的是,新興中產階級受到既自豪又不安的復雜心理所驅使。

Close to 30 percent of Brazil's new middle class owes its livelihood to the informal market,where income is irregular, safety nets are nonexistent,and opportunity for entrepreneurship is limited.

近30%的巴西新興中產階級都在非正規市場中謀生,收入很不穩定,缺乏社會保障網絡,創業機會極為有限。

Many have borrowed their way to higher living standards,one reason perhaps that 53 percent say they live in fear of unemployment,loss of income, or even bankruptcy.

許多人是通過借貸的方式來達到較高生活水準的,這可能是53%的中產階級說自己生活在對失業、收入減少甚至破產的恐懼之中的原因之一。

They have benefited from the explosion of private schools but have seen the overall quality of education plummet,eroding one of the classic middle-class paths to social mobility.

鑒于新興中產階級十分不穩定,他們影響政治變革的能力也將具有不確定性。

Indeed, some development economists argue that the poor will be a greater force for social change,but their ability to become a force for better government,greater freedoms, less corruption, and more economic liberty is much less certain.

一些經濟學家強調,窮人將成為推動社會變革的更強大的力量。發展中世界新涌現的消費人群也許在收銀臺上釋放了巨大的新能量,但他們不太可能成為推動政府改良、擴大自由、打擊腐敗以及提升經濟自由度的力量。

They have a very long way to go before becoming us.

但要成為我們,他們還有很長的路要走。

Now, with the Western middle classes sinking into debt and distress,many economists look to a new emerging-market middle class as the potential foundation for a new age of global safety and prosperity.

Now, with the Western middle classes sinking into debt and distress,many economists look to a new emerging-market middle class as the potential foundation for a new age of global safety and prosperity.

Now, with the Western middle classes sinking into debt and distress,many economists look to a new emerging-market middle class as the potential foundation for a new age of global safety and prosperity.

Now, with the Western middle classes sinking into debt and distress,many economists look to a new emerging-market middle class as the potential foundation for a new age of global safety and prosperity.