When analysts talk about the past three decades of Chinese economic growth it is often in reverential, quasi-religious terms. China’s 35 years of 9.7 per cent average annual expansion “is a miracle unprecedented in human history”, says Justin Lin Yifu, who was chief economist at the World Bank from 2008 to 2012.

分析師們在談論過去30年中國的經濟增長時,往往會使用滿懷敬意的、近乎宗教式的措辭。用曾在2008年至2012年擔任世界銀行(World Bank)首席經濟學家的林毅夫(Justin Lin Yifu)的話來說,中國在35年間實現9.7%的年均增長是“人類歷史上不曾有過的奇跡”。

The lifting of 400m to 600m out of poverty could possibly count as a miracle but the model of growth, and the expansion rates, are not unprecedented, even among China’s neighbours.

讓4億至6億人脫貧,也許可以算作一個奇跡,但這種經濟增長模式和增長速度并非不曾有過,其實在中國的周邊地區就不乏先例。

“We’ve seen this movie before – in South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Japan. We’re just seeing a bigger and more colourful version in China,” says Frederic Neumann, co-head of Asian economic research for HSBC. “Japan in the 1960s grew at 10 per cent a year and was considered the miracle economy of the time.”

“我們以前在韓國、臺灣、香港、日本看到過這一幕。現在只是在中國看到了一個更大、更豐富多彩的版本。”匯豐(HSBC)亞洲經濟研究聯席主管范力民(Frederic Neumann)表示,“日本在上世紀60年代每年增長10%,在當時被視為經濟奇跡。”

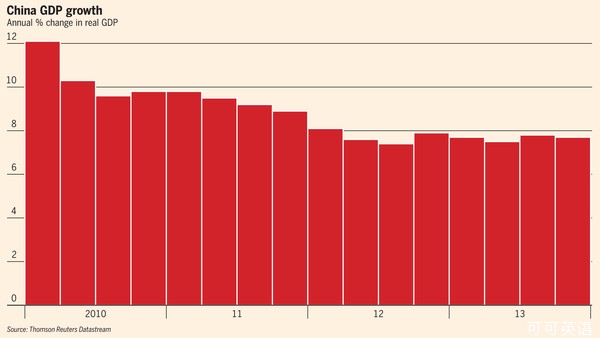

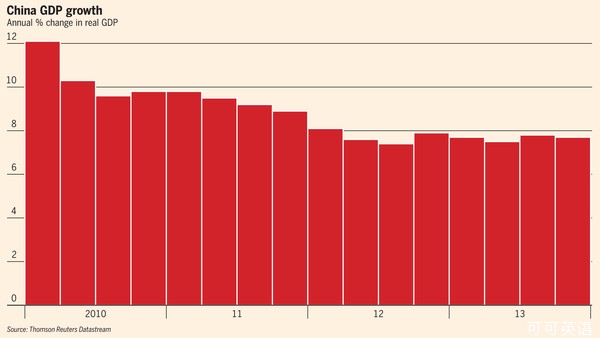

China’s economy expanded 7.7 per cent in 2013, government figures yesterday showed, on par with the revised 7.7 per cent growth rate for 2012. But most analysts expect growth to decelerate this year to its slowest pace in more than two decades. Many are starting to wonder if the similarities between China and its neighbours extend to their downturns as well as their booms.

昨日發布的官方數據顯示,中國經濟在2013年擴張了7.7%,與2012年修訂后7.7%的增長率持平。但多數分析師預計,中國經濟增速將在今年放緩至20多年來最低的水平。許多人開始揣測,中國與鄰近經濟體在經濟繁榮時期的相似性,會否延伸到經濟低潮時期?

As in most former high-growth Asian countries, the lift-off was driven by investment in cheap manufacturing for export, which was able to drive expansion for more than a decade.

正如大多數曾經高速增長的亞洲經濟體所發生的情況那樣,這種經濟騰飛主要得益于對面向出口的低成本制造業的投資,這種模式能夠在10多年的時間里推動經濟擴張。

Likewise, slowing export growth has been replaced in China by credit-intensive domestic investment, particularly in infrastructure and real estate. The next step in each of its more developed neighbours was an abrupt slowdown as overreliance on infrastructure investment reached its limits.

同樣,現在在中國,不斷放緩的出口增長也已被信貸密集型國內投資所取代,尤其是在基礎設施和房地產領域的投資。在中國周邊的每一個較發達經濟體,隨后發生的則是隨著對基建投資的過度依賴達到極限,經濟增長突然放緩。

“It’s not inevitable that China will also face a sharp correction as those other countries did but the danger is definitely there,” says Mr Neumann. “To think that the Chinese economy is immune to the same forces as other economies is to put misplaced faith in the idea of Chinese exceptionalism.”

“中國并非必然會像其他那些國家那樣面對大幅回調,但危險肯定是存在的。”范力民表示,“如果認為與別的經濟體相比,中國經濟對同樣的力量具有免疫力,那就有點過于相信‘中國例外論’了。”

The consensus forecast among private sector economists is for 7.4 per cent growth in 2014, the slowest growth rate since 1990, when China faced international sanctions in the wake of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre.

私營部門經濟學家的共識預測是,2014年中國經濟將增長7.4%,這將是自1990年(當時中國在1989年鎮壓天安門廣場抗議后面臨國際制裁)以來的最慢增速。

Of course, a larger Chinese economy growing at a slower rate contributes more to global gross domestic product than a smaller China growing faster. But even the most optimistic forecasters say Beijing must implement painful economic reforms just to maintain these lower, less miraculous, rates of expansion.

當然,規模更大的中國經濟以較慢的速度增長,對全球國內生產總值(GDP)所作的貢獻仍大于增速更快、但規模較小的中國經濟。但是,就連最樂觀的預測者也表示,北京方面僅僅是為了維持這種不那么帶有奇跡色彩的較低擴張速度,也必須推行痛苦的經濟改革。

The International Monetary Fund predicts average growth of about 6 per cent a year from now until 2030 under a best-case scenario where the government implements reforms to rebalance the economy.

國際貨幣基金組織(IMF)給出的最佳情形預測是,從現在到2030年,中國經濟有望實現大約6%的年均增長率——前提是政府落實旨在推動經濟再平衡的改革。

Top of the list is financial sector reform so the government can get a handle on China’s credit addiction and debt load. Total debt as a percentage of GDP rose from 130 per cent in 2008 to more than 200 per cent by the end of 2013, the kind of increase that has often preceded financial crises in other economies. Beijing is trying to rein in excessive credit growth and wasteful borrowing by local governments but it has to be wary not to tighten too much for fear of precipitating a crisis.

排在首位的是金融業改革,它將使得政府能夠應對中國的“信貸癮”和債務負擔。中國的總債務與GDP之比已從2008年的130%升至2013年底的逾200%;在其他經濟體,這種債務增速往往是金融危機的先兆。北京方面正試圖遏制信貸過快增長和地方政府的揮霍性借款,但它因為擔心引發危機而不得不防止收緊過頭。

While many of the reforms envisaged by its leaders will contribute to the slowdown in expansion, not all are anti-growth.

盡管中國領導人設想的許多改革將有助于放緩擴張,但并不是所有改革都是反增長的。

“The key for the leadership will be balancing the pro- and anti-growth reforms and implementing them in the right sequence,” says Stephen Green, head of research for greater China at Standard Chartered.

“對領導層來說,關鍵將是在促增長和反增長的改革之間把握平衡,并以合適的順序推行這些改革,”渣打(Standard Chartered)大中華區研究部主管王志浩(Stephen Green)表示。

“Anti-growth reforms include deleveraging and closures of overcapacity – laying people off from steel mills – while pro-growth reforms include opening of new sectors like telecoms, railways and financial services to private investment, promotion of service sectors and cutting of administrative licences and approvals.”

“反增長的改革包括去杠桿化和關閉過剩產能,比如鋼廠裁員;而促增長的改革包括將更多行業——如電信、鐵路和金融服務業——對民間投資開放,促進服務業發展,以及簡化行政審批要求。”

How fast the government can move ahead with its reform agenda depends on how comfortable it feels with slower rates of growth. For decades, China’s leaders have acknowledged that their unelected rule relies on continued high rates of economic expansion. In each of the past two years, slower growth in the first half of the year prompted Beijing to waver in its commitment to reining in credit-fuelled infrastructure investment and loosen policy to keep GDP growth from slowing too much.

中國政府能以多快的速度推進其改革議程,取決于它在多大程度上愿意接受經濟增速放緩。幾十年來,中國領導人已經認識到,他們的非民選產生的執政地位有賴于持續的高速經濟增長。過去兩年里,上半年較慢的經濟增長均促使高層動搖承諾(即遏制信貸驅動的基建投資),轉而放松政策,以保持GDP增長不致放緩太多。

If the government continues to turn the taps on and off, the much-vaunted rebalancing of the economy may be perpetually delayed and the eventual reckoning could be worse than the slowdown its leaders are trying to avoid.

如果中國政府繼續采用這種把龍頭打開和關上的做法,被大肆吹噓的經濟再平衡可能會被永久推遲,最終局面可能會比領導人現在試圖避免的增長放緩更加糟糕。