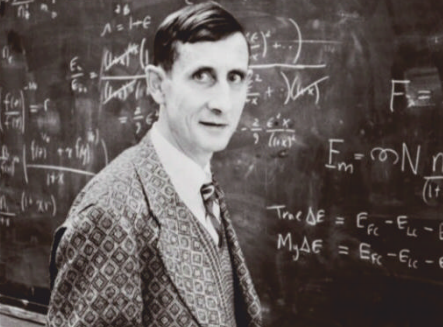

Despite a lack of credentials (he never got round to earning his PHD; friends joked that he was the world's most accomplished graduate student), he was plainly clever. By the age of five, growing up in Berkshire, he had tried to calculate how many atoms there were in the sun. His leisure reading as a teenager was Piaggio's "Differential Equations"; and he had solved that quantum electrodynamics puzzle, without pen or paper, while riding in a Greyhound bus.

盡管弗里曼缺乏資格證書(弗里曼從未有時間取得博士學位;朋友們開玩笑說他是世界上最有成就的研究生),但是他顯然很聰明。弗里曼在伯克希爾長大,5歲時曾試圖計算太陽中有多少原子。他十幾歲時的閑暇讀物是皮亞喬的《微分方程》;他在乘坐灰狗巴士時,不用紙筆就解開了量子電動力學難題。

His very cleverness, his vivid language and his faith in the potential of science—which marked him as it marked the century—meant that, even when his schemes were wildly bizarre, they were not dismissed. Colleagues respected him too much. And the schemes came thick and fast. He proposed using genetically altered trees to turn comets into places where humans could resume an "arboreal existence"; these trees would grow hundreds of miles high, until the comet would look like a sprouting potato.

弗里曼的聰慧,他生動的語言和他對科學潛力的信心——這是他的標志,也是這個世紀的標志——意味著,即使在他的圖式非常怪異的時候,它們也沒有被駁回。同事們太尊重他了。而且圖式又來得又快又密。他建議用基因改造過的樹把彗星變成人類可以恢復“樹棲生活”的地方;這些樹會長到幾百英里高,直到彗星看起來像一個發芽的土豆。

He also popularised a wild thought called the Dyson sphere, a gigantic shell made of pulverised asteroids that might be spread by a very advanced civilisation round its parent star to capture all its energy. (Looking for such structures and their infrared glow elsewhere in the galaxy, he argued, might be a good way to detect super-advanced aliens.) He imagined plants that could grow greenhouses round themselves, and genetically altered microbes that could harvest minerals and clear up plastic litter from space.

弗里曼還推廣了一種叫做戴森球的瘋狂思想 戴森球是一個由粉碎的小行星組成的巨大外殼,可能由圍繞其母星的一種非常先進的文明傳播,以獲取它所有的能量。(他認為,在銀河系的其他地方尋找這樣的結構和它們的紅外線,可能是探測超級先進外星人的好方法。)弗里曼設想過可以在自己周圍形成溫室效應的植物,還有轉基因微生物,它們可以收集礦物質,清除太空中的塑料垃圾。

譯文由可可原創,僅供學習交流使用,未經許可請勿轉載。