蘇聯(lián)舊事

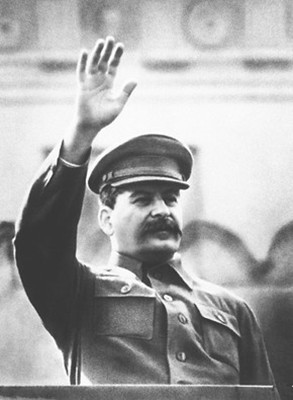

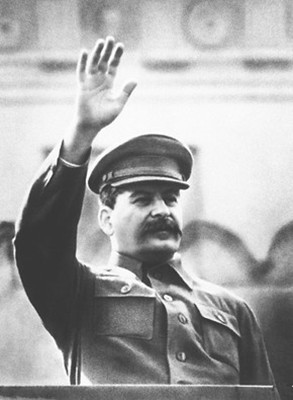

Stalin and his cursed cause

斯大林和他可憎的事業(yè)

High five for communism

為共產(chǎn)主義擊掌

Stalin's Curse: Battling for Communism in War and Cold War. By Robert Gellately.

《斯大林的詛咒》:熱冷戰(zhàn)期間為共產(chǎn)主義而戰(zhàn)斗。羅伯特蓋拉特萊著。

FIRST and foremost, Stalin was a communist, who believed that the sacred cause justified the most extreme measures: what non-believers would call unparalleled barbarity. This central message in Robert Gellately's masterly new book is an uncomfortable one for those who believe that Stalinism was an aberration, or a reaction to mistakes made by the West. It is facile to say Stalin was simply a psychopath, that he believed in terror for terror's sake, or that the Red Tsar's personality cult replaced ideology. A Leninist to his core, he was conspiratorial, lethal, cynical and utterly convinced of his own rightness.

首先,斯大林是一個共產(chǎn)主義者。他相信只要是為了神圣的事業(yè),采取最極端措施也是可以的。而不相信的人稱之為空前的暴行。蓋拉特萊最新的作品堪稱大師之作。文中表達的中心思想會讓一些人感到不安。那些人認為斯大林主義不合常規(guī),或者是對西方所犯的錯誤作出的回應。人們可以輕率地說,斯大林就是一個精神病,他為引起恐慌而信仰恐怖活動。或者說他用對“紅色沙皇”的個人狂熱崇拜取代意識形態(tài)。斯大林是徹頭徹尾的列寧主義者,他愛耍陰謀,心狠手辣,生性多疑,卻堅信自己事業(yè)的正義性。

“Stalin's Curse” draws mainly on German and Russian archives, plus numerous first-hand accounts, and the author's formidable interpretative skills. Unlike other biographies that have focused on the most sensational episodes in the dictator's life, it sets Stalin firmly in the historical context: the rise (and eventual fall) of what the author calls the “Red Empire”.

除了運用大量第一手記述資料之外,《斯大林的詛咒》主要參考了德國和俄國檔案。書中作者對史料的解讀展現(xiàn)出高超的技巧。與其他傳記聚焦這個獨裁者一生中最轟動的軼事不同,本書牢牢地將斯大林置身于在歷史大背景(作者稱之為“紅色帝國”的崛起,最終失敗了)

Mr Gellately's latest work has a good claim to be the best single-volume account of the darkest period in Russian history. It is part of a crop of excellent new accounts of the era. It sits well with Timothy Snyder's 2010 book, “Bloodlands” (about mass killings) and Anne Applebaum's “Iron Curtain” (which deals with eastern Europe after 1944 and which came out last year). It is also a worthy successor to his “Lenin, Stalin, Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe” (2008), which compared and contrasted the three monsters.

要說講述俄國最黑暗時期的單冊歷史書描述中最優(yōu)秀的,蓋拉特萊的新書當之無愧。它是記錄那個時代的諸多新杰作之一。這本書和蒂莫西 斯奈德2010年的新書《血色土地》(講述數(shù)起大屠殺)和安妮 阿普勒鮑姆“《鐵幕》(此書講述1944年之后的東歐歷史,去年出版)相得益彰。此書算得上蓋拉特萊的《列寧,斯大林,希特勒:災難的年代》的出色姊妹篇。后者比較了三個殘酷的領(lǐng)導人。

Stalin's supposed strategic genius gets short shrift, along with his generalship. Because communist doctrine said all imperialists were equal, Stalin failed to see that the Western powers were not the same as Nazi Germany, and might even be useful allies against it. For all his paranoia and cynicism, the Soviet leader was determinedly friendly to Adolf Hitler, apparently believing that close ties with the Soviet Union made a Nazi attack less likely. But Hitler saw it the other way round: relying on Soviet imports endangered his long-term goal of destroying communism.

人類們認為斯大林滿腹韜略和將才的天賦,本書作者卻不以為然。因為社會主義教條宣稱帝國主義者都是一樣的。斯大林沒能看到西方政權(quán)與納粹德國并非完全相同,甚至與西方政權(quán)聯(lián)盟可能對反納粹德國最有效。盡管偏執(zhí)又多疑,這位蘇維埃領(lǐng)導人卻堅定地對阿道夫希特勒表示友好,顯然是認為德國和蘇聯(lián)關(guān)系緊密,可以減少納粹進攻的可能性。但希特勒卻從另一方面看待此事:依賴蘇聯(lián)進口威脅了他摧毀社會主義的長遠目標。

Where Stalin excelled, again and again, was in ruthlessness and attention to detail. He paid minute attention to extending Soviet rule in places conquered at the war's end. He took great interest in details of science and cultural policy, fearing even the faintest breach in communist omniscience. The results might be disastrous: but they were in accordance with communist theory, which was what mattered.

斯大林次次出眾的是殘暴以及對細節(jié)的關(guān)注。在這場戰(zhàn)爭尾聲,他對蘇聯(lián)統(tǒng)治在被攻克地區(qū)的擴張給予了密切關(guān)注。他對科學和文化政策的細枝末節(jié)十分感興趣,甚至擔心自己的模糊會對社會主義者無所不知的形象造成破壞。其結(jié)果可能是災難性的,但再這些政策都與社會主義理論相符合 ,這是最關(guān)鍵的。

Mr Gellately, a professor in Florida, has a deft touch with detail. For all the havoc he wreaked on the countryside, Stalin knew next to nothing about it (he seems to have visited farms only once, in 1928). During their furious conquest of Germany, the Red Army soldiers avenged their homeland's suffering in an orgy of destruction. An eyewitness describes their taking “axes to armchairs, sofas, tables and stools, even baby carriages”. Individual stories are recounted with understated sympathy. But the scope of the suffering is inconceivable. An all but forgotten post-war famine in the Soviet Union killed 1m-2m people. Communism probably killed around 25m: roughly the same toll of death and destruction as that wrought by the Nazis.

蓋拉特萊,是一名佛羅里達的教授,善于挖掘細節(jié)。盡管斯大林在農(nóng)村造成了破壞,本人卻幾乎毫不知情(貌似他只在1928年參觀了農(nóng)場一次)。在猛攻德國期間,紅軍通過一系列肆意摧毀來為祖國曾遭受的苦難復仇。一個目擊者形容他們“用斧頭劈扶手椅,沙發(fā),桌子,凳子甚至嬰兒車”。個體的故事只是帶著輕描淡寫的同情色彩敘述著。但苦難的波及之廣是難以想象的。 一場快被遺忘的蘇聯(lián)戰(zhàn)后饑荒餓死了10到20萬人。共產(chǎn)主義可能導致了25萬人死亡:和納粹造成的死亡、損失數(shù)字大致持平。

Aside from the chief villain, Western leaders too come in for quiet but deserved scorn. Both Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman failed to grasp their counterpart's malevolence. Winston Churchill made casual deals that consigned millions of people to slavery and torment. The foreigners thought Stalin was a curmudgeonly ally to be coaxed and cajoled. He treated them as enemies to be outwitted. Far from provoking Stalin into unnecessary hostility, the Western powers were not nearly tough enough.

除首要的反面人物外,西方領(lǐng)導人也受到雖克制的但應得的蔑視。富蘭克林羅斯福和哈里S杜魯門都沒能洞悉與他們的對手斯大林的惡毒。邱吉爾隨意就達成了協(xié)議:導致數(shù)以百萬計的人遭受奴役和折磨。這個外國人認為斯大林是個易被哄騙和勸誘的,脾氣暴躁的同盟者。他對他們就像瞞騙敵人。西方列強不愿挑起斯大林的不必要敵意,更談不上對他采取強硬態(tài)度。

Some of the strongest passages of the book concern Stalin's final years: the sharpening contrast between his obsessive paranoia and his analytical powers; the looming anti-Semitism, and the beginnings of a massive new arms build-up. Little of that came to fruition, sparing the world untold new horrors. But what Stalin did achieve was quite bad enough.

書中涉及斯大林最后日子的段落是高潮:他的強迫性偏執(zhí)和超強的分析能力形成鮮明對比;骨子里的反親猶太人主義,一種大規(guī)模新式軍備逐步增強的開端。這些只有少部分實現(xiàn)了,使世界免于數(shù)不清的新恐慌。但已實現(xiàn)了的那些,卻是夠壞的了。